Update: There has been some recent research that suggests that while the timeliness of feedback is one aspect of good feedback, it may not be the most critical aspects of feedback. Awful feedback given immediately is much less useful than carefully constructed feedback given later.

Abstract

A review of the literature on the role of feedback in learning shows that student feedback is critical to student learning. Although different studies emphasis immediacy in feedback to different degrees, all of the studies reviewed agree that timeliness in feedback is important.

The Role of Immediacy of Feedback in Student Learning

Without feedback of any kind, we would not learn at all, period. We would end up doomed to repeat the same mistakes over and over again, as the fable of Sisyphus (Camus, A. & O’Brien, 1975) demonstrates. As teachers then, one of our primary roles for our students is to provide opportunities for feedback, preferably in different forms. Examining the literature on student feedback, we can see that this claim is supported.

According to Nicol and Macfarlane (2006, p7), there are seven principles of good feedback practice. Good feedback:

1. helps clarify what good performance is (goals, criteria, expected standards);

2. facilitates the development of self-assessment (reflection) in learning.

3. delivers high quality information to students about their learning;

4. encourages teacher and peer dialogue around learning;

5. encourages positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem;

6. provides opportunities to close the gap between current and desired performance;

7. provides information to teachers that can be used to help shape the teaching.

When Nicol and Macfarlane (2006, p9) clarify these expectations, they indicate that “high quality information” about student learning means “that feedback is provided in a timely manner (close to the act of learning production), that it focuses not just on strengths and weaknesses.” Quality feedback includes a provision that the feedback is provided close to when the students are learning the material.

Chickering and Gamson (1987, p2) also have seven principles of good practice in practice for education. They indicate that good practice in undergraduate education:

1. Encourages Student-Faculty Contact

2. Encourages Cooperation

3. Encourages Active Learning

4. Gives Prompt Feedback [emphasis mine]

5. Emphasizes Time on Task

6. Communicates High Expectations

7. Respects Diverse Talents and Ways of Learning

Note that here, Chickering and Gamson have indicated that feedback needs to be prompt to be included in their list of good practice for undergraduate education. It is fair to assume that good educational practices at an undergraduate level of schooling are also good practices at any level of schooling.

Learners themselves have an understanding of the importance of feedback in learning. According to a study done on the expectations of students as to levels of support provided by the educational service provider, Choy, McNickle, and Clayton (2009, p8), found that the services found most highly regarded were:

1. clear statements of what I [the learner] was expected to learn

2. helpful feedback from teachers [emphasis mine]

3. requirements for assessment

4. communication with teachers using a variety of ways, for example, email,

5. online chat, face to face

6. timely feedback from teachers [emphasis mine]

Note that feedback from the teachers was listed twice with the qualifiers of helpful and timely. Clearly the students in this study felt that feedback was important enough to mention twice.

McTighe and O’Connor (2005, p5) reiterate from Wiggins (1998) that “To serve learning, feedback must meet four criteria: It must be timely [emphasis mine], specific, understandable to the receiver, and formed to allow for self-adjustment on the student’s part.” They have only four requirements for feedback, and the first of these they list is how timely the feedback must be.

One could argue that timely feedback is most critical in student learning. “[T]imely, detailed feedback provided as near in time as possible to the performance of the assessed behavior is most [emphasis mine] effective in providing motivation and in shaping behavior and mental constructs” (Anderson 2008). Students need the feedback for learning to happen near to the event of learning, according to Anderson (2008), in order to learn effectively, which is what he means by “providing … mental constructs.”

If we view the analogy of learning a physical act, we can see how obvious it is that timely feedback is important. Although feedback from the learning of sport, or even the act of walking is not necessarily directed by teacher, the very world around us provides us with feedback. If we fail to walk properly, we fall down! Kick the ball with your toe, and it is sure to go over the goal. We learn physical actions very quickly because we receive lots of timely feedback about everyone of our actions. The only physical actions which are difficult to learn for some people, assuming capability of performing the action, are the ones where the feedback is delayed.

It is clear that any informed educational practice should take into account how feedback will be provided to the students. Feedback needs to be timely and relevant to the learner’s needs in order to be effective. Educators must therefore provide assessment opportunities for students with timely and relevant feedback built into the assessments or these assessments are limited in value.

References

Anderson, T. (2008). “Teaching in an Online Learning Context.” In: Anderson, T. & Elloumi, F. Theory and Practice of Online Learning. Athabasca University.

Camus, A. & O’Brien, J., (1975). The myth of Sisyphus, published by Penguin books

Chickering, A. & Gamson, Z., (1987) Seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education, AAHE bulletin, 39, 3-7

Choy, S.; McNickle, C. & Clayton, B., (2009). Learner expectations and experiences. Student views of support in online learning, National Centre for Vocational Education Research

Higgins, R.; Hartley, P. & Skelton, A., (2002). The conscientious consumer: reconsidering the role of assessment feedback in student learning, Studies in Higher Education, Routledge, 27, 53-64

McTighe, J. & O’Connor, K., (2005), Seven practices for effective learning, Educational Leadership, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. 63, 10-17

Nicol, D. & Macfarlane-Dick, D., (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice, Studies in Higher Education, Routledge, 31, 199-218

Wiggins, G., (1998). Educative Assessment. Designing Assessments To Inform and Improve Student Performance. Jossey-Bass Publishers

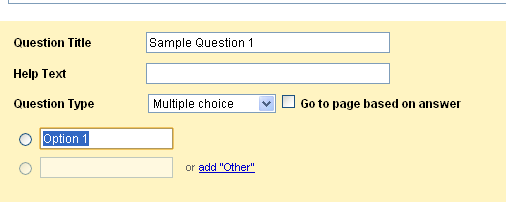

While constructing your form, you are going to alternate between adding page breaks and adding multiple choice questions. Adding a page break separates the form into multiple pages, and allows you to add a new title for the page and new text for each page. Each page will also need a multiple choice question, unless the student only wants the reader to move onto the next page.

While constructing your form, you are going to alternate between adding page breaks and adding multiple choice questions. Adding a page break separates the form into multiple pages, and allows you to add a new title for the page and new text for each page. Each page will also need a multiple choice question, unless the student only wants the reader to move onto the next page.  Students need to be in contact with other people on a regular basis, like all human beings, so the regular school house is not going to be abandoned. However much more space needs to be included in these schools for students to do independent work. The school of the future may end up looking more like the progressive offices of the present. The design of Google’s offices for their programmers are innovative and interesting, and although they may not exactly look like what you would expect a school to look like, a lot of the features of their work space are useful for education.

Students need to be in contact with other people on a regular basis, like all human beings, so the regular school house is not going to be abandoned. However much more space needs to be included in these schools for students to do independent work. The school of the future may end up looking more like the progressive offices of the present. The design of Google’s offices for their programmers are innovative and interesting, and although they may not exactly look like what you would expect a school to look like, a lot of the features of their work space are useful for education.

Just recently we had a very different type of auction at our school. Some teachers and many of the 12th grade students auctioned off various services for charity. For example, one of my colleagues agreed to dress up in drag and take some kids for an ice cream. Another pair agreed to set up a pizza lunch for the kids. The funds at the end of the event are going to our global humanitarian fund.

Just recently we had a very different type of auction at our school. Some teachers and many of the 12th grade students auctioned off various services for charity. For example, one of my colleagues agreed to dress up in drag and take some kids for an ice cream. Another pair agreed to set up a pizza lunch for the kids. The funds at the end of the event are going to our global humanitarian fund.