If you don’t have time to blog about reform, just add your voice to the Voicethread below and answer a simple question:

What do YOU think should be done about reform.

(original photo by Aussiegall)

Education ∪ Math ∪ Technology

If you don’t have time to blog about reform, just add your voice to the Voicethread below and answer a simple question:

What do YOU think should be done about reform.

(original photo by Aussiegall)

Today I participated in an event which was held simultaneously held in 16 other cities around the world organized by 350.org and the Vancouver Public Space Network.

Today I participated in an event which was held simultaneously held in 16 other cities around the world organized by 350.org and the Vancouver Public Space Network.

On a very cold day in Vancouver, we headed to David Lam park and stood around a field holding green umbrellas. We arrived early in the morning and draped green across our umbrellas and held them up in the air. Our objective was to focus attention on climate change and participate in a community building activity.

My son was a little trouper for most of the event, but eventually we went to a nearby coffee shop, grabbed a hot chocolate to fortify ourselves, and then came back to the field just in time to be photographed from space and from an airplane.

Human beings are capable of organizing themselves into such intricate and amazing patterns. This particular project was dealing with climate change, which is a serious issue for our planet. The reform over how we utilize resources on our planet is under way and although it has not made enough of an impact to slow climate change, already there are many things that we do differently because of it.

Similarly our entire education system is a such an amazing machine when you look at all of its pieces. So many different people have to cooperate to make our education system run.

There is something fundamentally wrong with the machine though because it is no longer functioning as it should. The machine was built for a very different world than the one in which we live. Just like we need to change how we consume everything our planet has to offer, we need to change how we educate our youth. The changes that are needed for either problem are not small, they will require wholesale rethinking of our resource and education systems. We need to rebuild our machines.

The problem is that both of these machines have a tremendous amount of inertia behind them. Most people who are bound by these systems can’t see a different way of doing business. Worse, even those who have the ability to step outside the box and visualize these problems from a different perspective cannot agree on what that perspective should be. We are trapped by our inertia and it will only be through great effort and quite possibly sacrifice that we will solve either of these problems.

We must solve these problems. It is not acceptable that we continue to plunder our planet the way that we are whether or not you believe that we are causing great damage to our climate. It is similarly not acceptable that our schools are not preparing our students properly for life. The machines of education and resource management do not require some grease or some minor fixes to start working again. Both of them need to be rebuilt completely.

Thankfully, there is hope. So many people came together today to support a climate change awareness initiative and so many continue to work on solving this important problem. Similarly there are so many educators now who are aware of the issues we are having in education, and who are working to try and affect changes in their schools. The only question will be, will we be able to make the changes we need before both systems collapse completely?

There are lots of enormous flaws at the root of the current effort to evaluate teachers across the US. We could talk about how each teacher serves a much different population, or how the resources which are provided to each teacher are different because of the wealth of their educational community, or how a poor administrator can influence teacher evaluations, but there is a deeper flaw, one based on a more mathematical argument.

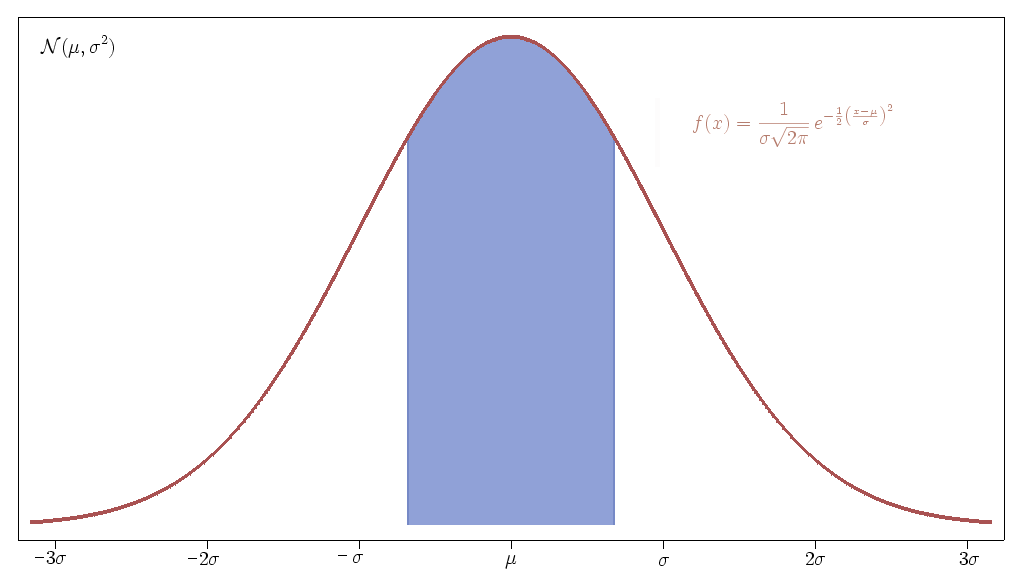

Imagine we ranked all of the teachers according to how much material they covered (which is essentially what grading them using standardized assessment scores from their students do), much like the current SAT system ranks students, and then graphed how many teachers were at each rank. The graph would look very much like the following.

This is called the normal distribution in statistics. The function written at the top doesn’t matter very much. What matters is that μ is the mean (average) of the distribution and σ is what is known the standard deviation (read this explanation if you are confused). μ is measure of where the center of the data is, and σ measures how spread out the data is.

A couple of important facts to know about this graph is that about 68% of the teachers will be within one standard deviation of the mean and that just over 95% of teachers will be within two standard deviations of the mean. This means that the vast majority of teachers will be ranked near the middle of the graph. Teachers within one standard deviation of the mean could be considered average, and teachers ranked below two standard deviations of the mean would be in the bottom 2.3% of the teaching profession. These are the people that typical reform efforts like to target and were recently "exposed" in the LA Times value-added assessment project.

Now let’s suppose we managed to improve the education system in the US a whole bunch. In fact we manage to improve it so that instead of each student learning one years worth of material in a year, they learn two years worth of material! Wow! Good for us! What would happen to the picture above then?

Well it turns out nothing would happen at all. The reason is because the picture above represents a relative ranking between teachers and there will always be teachers who rank lower than other teachers. No matter how much we improve education, the picture above will always remain the same, with one exception. If every teacher was ranked equally, then the picture above would look more like a very thin bar sitting above the mean. I don’t think that will ever happen though and it would certainly be a pretty boring education system. Imagine if students never had a favourite teacher; who would want to join the profession then?

The other point to bring up is that if we supposed that the teachers at the mean of the distribution teach what we call a "year’s worth of material" then as we improved teacher quality and this mean rose, then so would what we defined to be a "year’s worth of material." We’d always be stuck bemoaning the fact that there are teachers who can somehow only cover half a year’s worth of material and other teachers who can cover two year’s worth of material. The amount of material to cover would just rise.

The flaw is that the more material we try to cover each year, the less room there would be for the individuality and creativity which is so important to the teaching profession and to education in general. I’d like to see a slightly different way of assessing teachers. Let’s assess teachers based on their professional relationships with each other, based on the rapport they develop with students, on how willing they are to share their expertise, on the quality of the research they have done, and a host of other factors which cannot be measured by a test, or conveniently broken down into a normal distribution.

Let’s assess each teacher individually.

Knowledge has always been advanced in human culture based on the ideas of others. Our entire knowledge structure today is based on what we, as a species, learned in the past. Each generation learns what the previous generation already knew, and then expands upon this base of knowledge for the next generation.

A problem with this system is that the amount of knowledge one must know before one can make an original contribution to the existing knowledge base increases with each generation. In other words, each generation spends more time than the previous generation learning about existing knowledge before adding their knowledge to the pool.

One way we have already begun to combat this problem is with increasing specialization. Instead of trying to learn everything from the previous generation, each individual learns only what is necessary in order to be able to advance the knowledge base and most individuals do very little to advance the knowledge base themselves, but instead provide the necessary support for our knowledge based society.

Here’s an example of the problem with specialization based on the field of mathematics. It used to be that almost every mathematician was an amateur without a lot of formal university training. Euclid’s Elements was a textbook for mathematicians for about 2000 years. Why was this possible? Well because quite simply, there wasn’t enough mathematics to be learned that you couldn’t contain a significant chunk of it in one book. So being an amateur mathematician was possible because you could read a few books about mathematics and suddenly be able to produce original ideas.

Now there are hardly any successful amateur mathematicians although many people still dabble in their spare time in mathematics. In this case, I define a "successful" mathematician as someone who has in some way advanced the pool of mathematical knowledge. The lack of amateur mathematicians is largely due to the fact that in order to be able to advance mathematics, one has to know quite a lot of mathematics, more than is really possible for the typical person. I can’t pick up a few books and suddenly be at the edge of what is known, instead I need years of training before I will reach that point, especially in the field of mathematics. Most of what we teach at the high school level, for example, is mathematics that was invented more than 300 years ago.

We have essentially hit the limit for what an amateur mathematician is capable of producing. We should expect only highly specialized mathematicians will produce new knowledge in the area of mathematics for the rest of our future as a species. This limit will eventually increase so that eventually no one will be able to add to the field of mathematics.

Increasing specialization can only take us so far in allowing us to keep increasing the knowledge base. Humans are an insatiably curious species, so it is far to assume that for most of us, increasing what we know as a species is a worthwhile goal. So what are we to do when it consumes an entire human lifespan just to learn enough to be able to add a small piece of knowledge to what we understand?

There are still a few areas where one can begin to add to existing knowledge without an enormous amount of investment in time learning the existing knowledge base. Interestingly enough, one of these is education itself. If we measure the complexity of a subject by the average number of years one needs to go to school before one can add to the existing knowledge base, then the field of education would be considered fairly simple. You can go to school for a mere 5 or 6 years after high school and be able to enter a classroom and learn about how people learn first hand. Add a year of learning about how to do research in the field of education and suddenly you can become someone who adds new knowledge to the pool of what is known about education.

Why is this true? Well, quite simply, as a species we are still mostly in the dark about how we learn, and what the best methods are for helping students learn. We have many theories about how learning works, and how to best apply it, but none of them has emerged as a definitive "best" theory.

Our ignorance as a profession of how people learn is astounding to me. It simply amazes me that we are still having a debate about whether having groups or not is best for learning. We still wonder if the introduction of technology in the classroom is worth it. Should kids be streamed or not? Is assigning homework right? How much homework is best? Home-schooled or not? Remember that we are the same species which is capable of sending someone off of our planet and then bringing them back, and that we did that more than 40 years ago! Why can’t we figure out how to make our education system work for everyone?

Another way to improve the odds of any individual person adding to the knowledge base besides increasing specialization is to greatly improve the efficiency of their education. Even a small improvement in the speed at which people learn the existing knowledge base could lead to years of extra time as a productive mathematician for example. If we knew more about how people learned, we should be able to translate this knowledge into improved opportunities for learning more about how the universe works, simply because we would be providing more time for specialists to work in their chosen field.

Furthermore, many people never have the opportunity to even consider adding to the pool of knowledge because they end their own education out of boredom! How many geniuses have we lost because of the way we constrain people so much in our system of education? Just improving graduation rates and allowing more personalization of education could do a lot to improve the efficiency of education.

We should be investing in our education systems more. We should invest heavily in research in education because that is an area where we can actually make an enormous improvement in the quality of education and eventually in how much we know as a species. A small gain in improved efficiency of our education system could lead to a large gain in end research because of the exponential effect of knowledge acquisition.

Here are eight videos to help teachers get started with using Twitter. The idea for these videos is to make them short and to the point and provide specific instructions on how teachers can use Twitter.

How to sign up for Twitter

Verifying your email account with Twitter

Customizing your profile on Twitter

How does Twitter work?

Installing Tweetdeck

Customizing Tweetdeck

Finding people to follow on Twitter

Participating on Twitter

>

My friend, whom I met when I worked in an international school in Bangkok, worked in a bilingual school in Thailand before the school where I met him. He said it was an interesting job, but he was glad to be working at a school with a different emphasis.

The school he worked at had pretty good test results, some of the best in the country. Students would consistently score well on the state standardized tests held all over Thailand. So my friend went to observe the best teacher in the school, as measured by how well her kids did on the standardized tests.

He told me that he watched 2.5 hours of this teacher reading out answers from previous standardized tests. She did nothing else! She didn’t ask any questions, she didn’t check for any understanding from the students, she spent 150 minutes going through questions and their solutions on a multiple choice exam.

What type of education system do you want? Is this what we want to emulate? Time and time again I remind myself how grateful I am to work in the International Baccalaureate framework where the only year I have to worry about a standardized test is at the end of 12th grade. Fortunately the exams at the end of the IB program are at least well written.

I just read this article from 2007, originally posted in the Boston Globe, but available here online. The point of the article is that participation in an Arts class helps students learn skills which may not be present elsewhere in their school as a result of a narrowing focus of schools on standardized testing. To summarize the article, students can learn reflection, "such skills include visual-spatial abilities, reflection, self-criticism, and the willingness to experiment and learn from mistakes" (Hetland & Winner, 2007).

It sounds to me like this list of skills closely resembles what we would consider critical thinking skills. Certainly it is an important set of skills and if this is the only place students are learning these skills, then Arts classes are critically important. However, I know that I teach these skills in my own academic area of mathematics, and that this is possible for me because I do not have to focus on a huge standardized test at the end of the school year.

In my mathematics class students are expected to write out their solutions to problems, and to reflect on what we do. Students take turn blogging about what happened in class, and commenting on each others’ summaries. Assessment is done using projects for which students are given time to detail complete solutions, and more importantly detail the thinking the students did to arrive at these solutions. Students have to evaluate their own work, and look for ways to improve it.

We take the time to do experiments in class to verify accuracy mathematical formulas. For example, we will go out to the soccer field and use cones to create right triangles, and then compare the actual lengths of the triangles to what trigonometry and the Pythagorean theorem say the lengths should be. We talk about experimental error, and the importance in accuracy of measurements. Students whose results differ greatly from the theory go back and do it again. If no one in the class were able to achieve the theoretical results, we would revise our experiment as a class and do it again. All sorts of mathematics can be taught through experiments and I find these experiences invaluable for the learning of the students.

Fortunately at the school I work at, Arts education is not in danger. We are a small private school and our head has recently invested in our students’ learning of art by hiring a full-time learning specialist for art. However I know this is not typical of schools, more and more Arts and Music are being removed from schools because of budgetary concerns and a desire to improve students’ performance on standardized testing. There just isn’t the time to devote to the Arts in the school-wide curriculum.

You can change your own classroom so that the Arts is embedded in what you do if your school district is too short-sighted. Critical thinking skills are too important to be discarded in favor of standardization of education.

Here is a great video shared on the Edweek blog.

This video should be something to show your staff at the beginning of the year. In fact, I’d like to make the focus of my training next year on building personal learning networks for the teachers, so that they see the value of their PLN. Some of the staff at my school are connected with teachers from other schools and other parts of the world, but most are not except in limited ways. More than anything else, I’d like my staff to see the value in creating their own learning network.

You should read the entire blog post on the Edweek blog and then decide how you will start your school year.

This afternoon I had a great conversation with David Miles and Fred Mindlin. David works as an Academic Coordinator in a private school in Dhaka, Bangladesh and Fred works as an educational consultant for the Central California Writing Project.

This afternoon I had a great conversation with David Miles and Fred Mindlin. David works as an Academic Coordinator in a private school in Dhaka, Bangladesh and Fred works as an educational consultant for the Central California Writing Project.

Both of them are extremely articulate and intelligent people who have a lot to say about education. I’ve known David for about 5 years now ever since we worked together in London, and I met Fred for the first time this afternoon.

I asked David through Skype, and I invited Fred through Twitter, and we all met in a Skype group chat. We decided to continue the conversation from #edchat and talk about educational reform.

This idea for a Conversation With Educators is from the podcast @betchaboy does, The Virtual Staffroom and is something I hope more teachers do. Talking with educators from around the world about what we do is a terrific experience. I hope to chat with more of you next week.

For now you can listen to this podcast episode below, or subscribe to this podcast in iTunes here. This podcast is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike license so please feel free to remix it and share it, so long as you give proper attribution to the original work.

Listen here: here

For those of you who are curious about the production of this podcast, it was recorded using a program called Skype Call Recorder on Windows, and slightly edited using Audacity.

A common problem that is discussed on Twitter between educators is that they don’t have full access to the Internet due to a filter installed either at their school or at the district level in their area. There are a number of arguments for and against the existence of these filters, summarized in the table below.

| Arguments for Internet Filters | Arguments against Internet filters |

| They satisfy need for control over what kids do in school. | They don’t teach responsible Internet use. |

| They prevent students from accessing sites which could be dangerous. | Useful tools are blocked. |

| They block access to social networking sites that may result in cyberbullying. | They cause network lag and slow down access to the Internet. |

| They make it easy to comply with educational regulations and laws involving Internet use by students. | They are easily circumvented anyway. Google “unblock websites at school” or “proxy servers unblock websites” |

| They teach kids how to avoid obstacles rather than how to solve problems. | |

| We are not teaching real life skills then, real life does not come with filters | |

| Internet filters tend to most often filter content for the teachers rather than the students: they know how to get by them. | |

| Within five years, the idea of an Internet filter will be antiquated. With the development of 4G networks and the growth of smartphones, it’s only a matter of time before the vast majority of students have unfiltered access to the Internet in their pockets, whether IT dept’s like it or not. | |

| Many school districts have removed Internet filters with no ill effects. | |

| They create an artificial, limited research environment that will not help them when they move on to jobs or higher ed. | |

| The prevent valuable learning experiences about the risks involved with the Internet from taking place. |

This document was produced by the collective wisdom of a few educators from #edchat working together. Our objective is to summarize all of the arguments for and against Internet filters in schools. The idea is, if we have the information and the argument worked out, our individual discussions with our local administrators will be a lot easier.

Most of us who chat on Twitter think that the Internet filters aren’t accomplishing their goal, which we think is to keep our students safe. What do they accomplish then? Mostly keep kids from making mistakes in school where they can be assisted with the consequences of their mistakes, and they prevent students from connecting to the most useful resources they could be using.

If you want to participate in the creation of this document, please feel free to add your thoughts here.