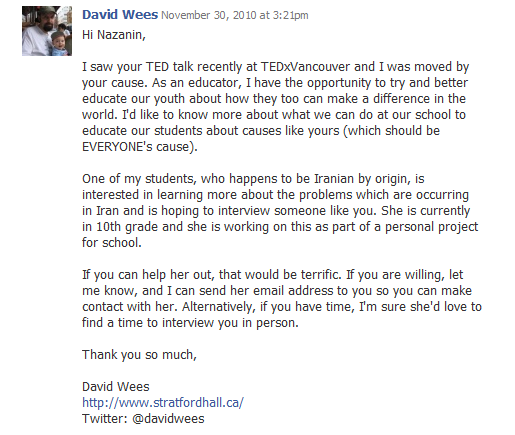

Thank you to @gcouros, @shannoninottawa and @stephen_hurley for sharing this fantastic TED talk with us on Twitter. It is definitely worth the watch.

So how does this talk apply to education?

There is a growing group of educators who believe that there is a problem with the US education system. There is also a growing group of people who are not educators who believe there is a problem. The US public, caught in the middle, has to make a choice between these two groups since the message they are sending out is quite different.

One group believes that students deserve good schools with good teachers, and that the best way to accomplish this is by making teachers more accountable for what they do, and applying free market philosophies to both schools as a whole, and specifically to teachers. The invisible hand of Adam Smith’s economic model will force schools into innovation and improvement, provided we remove the barriers of unionization and past "bad" contracts from schools. Merit pay will allow teachers to work harder to achieve better goals for students, and Race to the Top will make states compete for money, which will force them into a marketplace of a kind.

The other group believes that schools are becoming overly regimented and that there are too many rules on how they are supposed to be run, and too many accountability measures. They believe that these accountability measures, generally standardized tests, are slowly forcing schools to teach to the test in order to keep their funding. They believe that there is a wider experience that schools can offer than what can be measured on a standardized test. They also believe that the issue of failing schools comes to inequality in funding of schools, and more importantly the desperate inequality that exists in the US economic model. While the US is considerably richer than the rest of the world, the vast majority of that wealth is held within just a few people’s hands.

The problem is, if you belong to the second group anyway, is that the first message is gaining in strength. I believe that this is because the non-educator reformers have answered the why question with the parents of the US. They can point to a perceived failure in the system and then explain from the why, their how, and their what. They have a message which is compelling to many people but I believe that their solutions won’t work. The second group of people has suggestions for what, and for how, but their why is for some reason less compelling.

The solution the second group is offering is not going to work. They want to turn education system into a free market, but the market isn’t free if it is regulated, which is what the accountability measures they introduced with NCLB do. Maybe the premise that you can apply economic principles effectively to schools is flawed?

Suppose we did apply a true free market approach to schools. We’d remove all regulations which would hamper schools and then fund schools based on market principles. Good quality schools would cost more, poor quality schools would cost less. Families would sue schools which were too unsafe, and schools would naturally tend toward offering choices that encouraged kids to attend. Some schools would look for corporate sponsorship to help them. McSchools anyone? Each family would have to decide for themselves what constituted a quality school and make decisions about where they would send their children.

The problem is that we would see legions of schools do things which look good, and are easy for parents to measure, but which are pedagogically unsound. Deciding on how effective a school is a difficult task, one most parents would find daunting if not impossible. They would have to rely on visiting schools and taking a look around to see what the school is doing. In any case, I think it would fail, and lots of kids would be harmed in the process.

The real question is, how can that first group of people change our approach and sell our (I think you know by now which group I support) vision of what schools can be? How can we find a reason why schools need to change which will resonate with parents? I think too often we focus on how we would like schools to change, and what steps we would take to make those changes, and that the important reason why those changes need to happen is lost. We are being beaten badly in the US court of public opinion, and we need to step up our game.

For those of you who wonder why I, as a Canadian educator, am so passionate about the education debate in the US, you just need to remember how often our politicians have looked south of our border for solutions. I’m not interested in any of the current US style of reforms taking root here in Canada.