I’ve been reading about people trying to implement a paperless classroom, and it occurred to me that there are plenty of things you can do to implement this type of classroom, without using a lot of technology. You don’t need a 1 to 1 laptop program at your school to make it a (nearly) paperless classroom.

First buy some whiteboard material from your local carpentry supply store. Cut it up and make pieces about two feet (60 cm) by three feet (90 cm) in size.

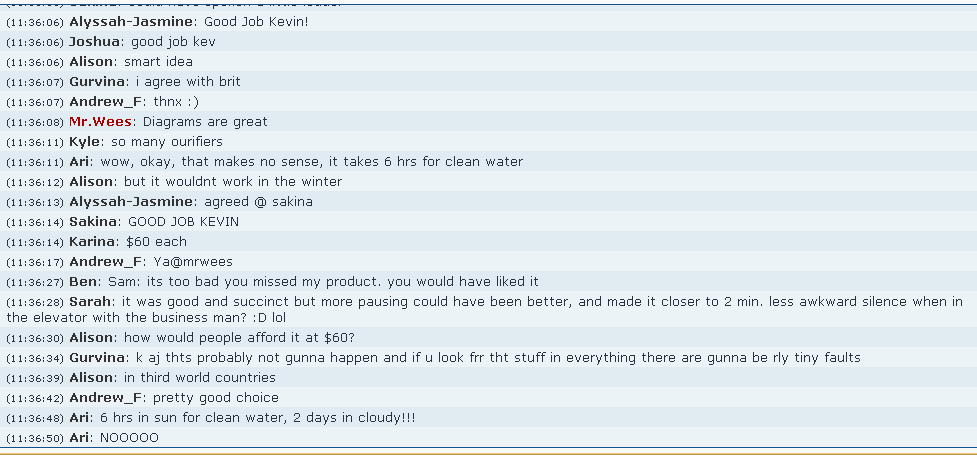

Here is an example of a classroom run using these whiteboards.

Having some larger whiteboards on which to share instructions or information is useful. Instead of handing out sheets of paper to students, most of what you will share will go on these whiteboards. I used to write down instructions for a project, or practice questions, or discussion ideas up on a whiteboard before school and when the particular class came in, I would put out the appropriate whiteboard. Doing this will eliminate the worlksheets from your classroom.

Next, find 3 or 4 desk-top computers to place somewhere in the back or side of your classroom, or even better separate them around the classroom so that students can crowd around them when necessary. These are your research stations and the places where students will create permanent digital copies of their work. An organization like Free Geek can help you reduce the cost of purchasing these, or you may even be able to find corporation to make a donation. It is important that at least one of these computers is reasonably decent and has an Internet connection, but the other ones don’t have to be awesome. It is amazing how much utility you can get out of an old computer when it’s running a low memory operating system like Ubuntu.

Having a document camera, or a projector hooked up to the one of the computers in the room would be useful, but not critical. You can see from the picture above that the whiteboards are large enough that when students are sharing their work, they can just hold up the whiteboard and let everyone see it. Alternatively you can treat the sharing of work as a mini-fair where each group takes a turn looking at a few other group’s work.

It would also be a good idea to equip this classroom with at least 1 or 2 digital cameras. These can be useful to take pictures of the work the students have done on the whiteboards. You can designate one of the computers as your media storage computer and upload the pictures to this computer since you will want some record of the student’s work for later.

You will also need some notebooks for the students to record other work, particularly in writing-rich classes. In some subjects you may find that the notebooks don’t see enough use to be needed, but in others they will fill up quickly. This is where most of the paper you will use in your class will be. The notebooks will be the place where individual reflection will take place and can either be shared or not shared, depending on your preference.

Another piece of the puzzle will be a library of books on the back wall, relevant to your subject area. This way students can do “off-line” research. Yes, some of the books will be woefully out of date, but if you have a variety of books, you can help kids understand that they need to examine multiple sources, and not just accept the first thoughts on a subject they find.

Most of the work students will do will happen on the whiteboards and will disappear forever after it has been erased from the boards. Some of it will be saved on the computers as a picture taken of the whiteboard. Some of it will be transcribed to the computers as you and the students decide on what summative assessments you will include.

The type of work students will do will be collaborative. Most of your assessment will be formative as you move around the room to ensure both that the students are on task, but also that they are meeting your shared expectations. Your summative assessments will either be recorded in the notebooks, or on the computers. You can use workstations as a way to differentiate your work, and to ensure that not everyone “needs” the computers at the same time.

The (nearly) paperless classroom starts with the assumption that not every piece of work students produce is worth saving forever. Most of it is just them sharing their thoughts. Think of the notebooks and workbooks your students currently have, and the notes that they take. 99% of that work will never be looked again once it is completed. It is only as small percentage of work that needs to be immortalized on paper.

Change your mindset that the paperless classroom needs a lot of technology. It doesn’t. It needs a transformation of pedagogy from teacher centred and content focused to student centred and a focus on developing skills.

Please share any other ideas you have on implementing the (nearly) paperless classroom.