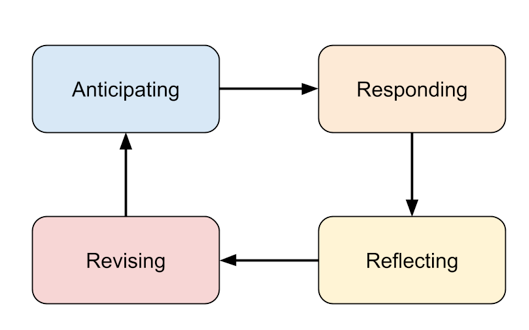

A recent analysis by David Blazar has stirred up some interest about Ambitious Teaching. But what exactly is Ambitious Teaching?

According to Elham Kazemi, Megan Franke, and Magdalene Lampert:

“Ambitious teaching requires that teachers teach in response to what students do as they engage in problem solving performances, all while holding students accountable to learning goals that include procedural fluency, strategic competence, adaptive reasoning, and productive dispositions.”

While this defines some aspects of Ambitious Teaching, this is not a sufficient definition such that any two observers would agree that an episode teaching observed was Ambitious.

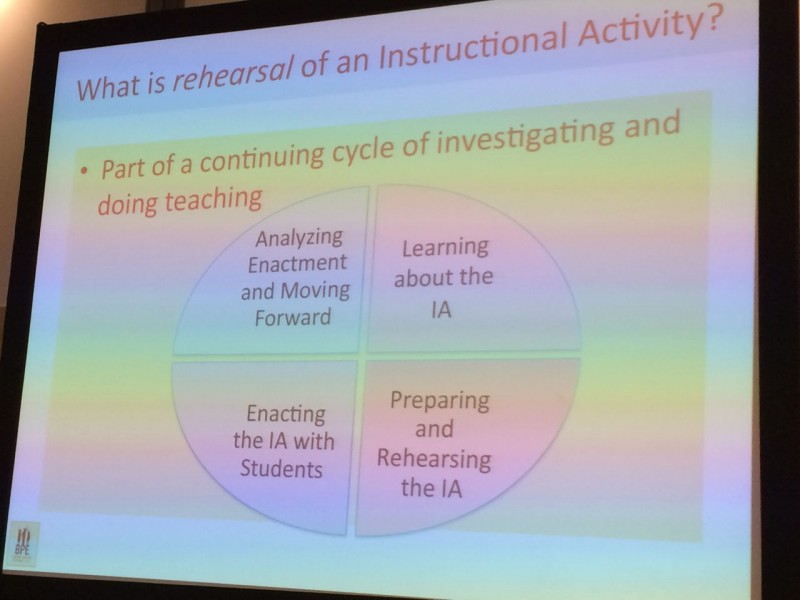

In this same paper, E. Kazemi et al. go on to talk about instructional activities they are teaching to pre-service teachers which:

- make explicit the teaching moves that are implied in the kinds of cognitively demanding tasks that are found in curriculum materials available for use by novices;

- structure teacher-student interaction using these moves in relation to teaching the mathematical content that students are expected to learn in elementary school;

- enable novices to routinely enact the principles that under gird high quality mathematics teaching including:

- engage each student in cognitively demanding mathematical activity

- elicit and respect students’ efforts to make sense of important mathematical ideas

- use mathematical knowledge for teaching to interpret student efforts and aim for well-specified goals

- be generative of other activities by including the teaching and learning of essential teaching practices (high leverage practices) like explaining, leading a content-rich discussion, representing concepts with examples, and the like (Franke et al., 2001).

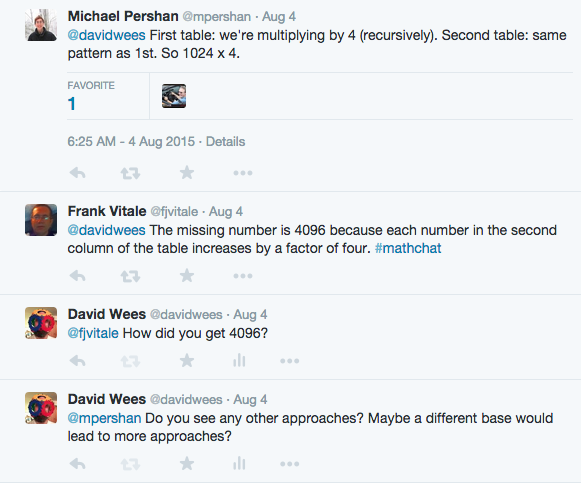

In his recent analysis, D. Blazar uses a research instrument which he separates into two aspects, one of which called “Ambitious Mathematics Instruction” positively correlates the following teaching practices with student performance on an assessment given to those students.

- Linking and connections

- Explanations

- Multiple methods

- Generalizations

- Math language

- Remediation of student difficulty

- Use of student productions

- Student explanations

- Student mathematical questioning and reasoning

- Enacted task cognitive activation

From this we can infer that these labels describe teaching practices which are part of Ambitious Teaching. We can generalize these practices to other content areas, although the practices will look different in those different content areas.

Dylan Kane unpacks one aspect of Ambitious Teaching, teaching to big ideas, which is about making connections between different ideas rather than treating each lesson as being in isolation from each other lesson.

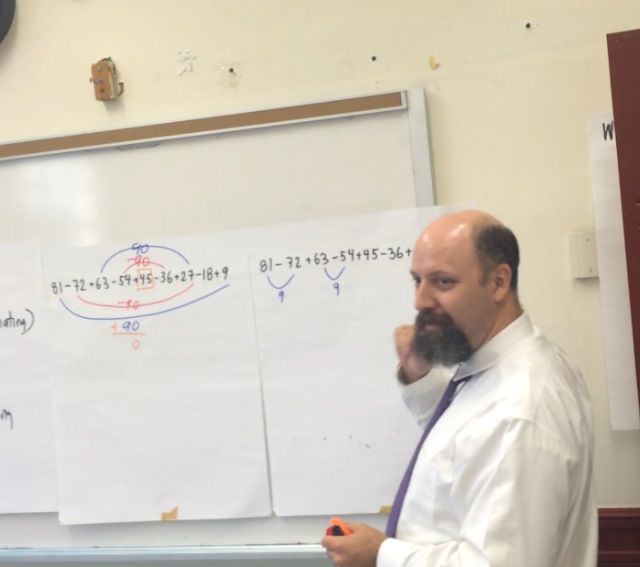

Photo of me leading a whole class discussion while annotating student strategies.

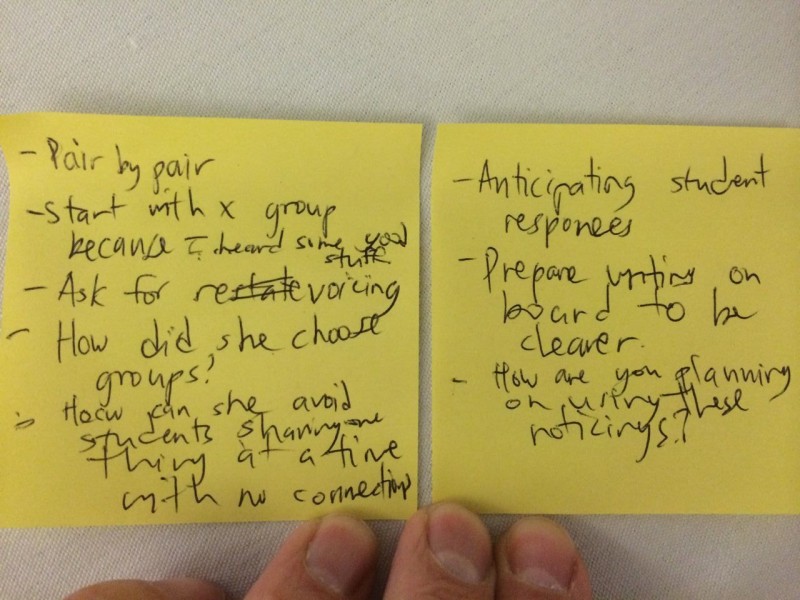

One key element that distinguishes Ambitious Teaching from other teaching is that ideas that emerge in class are built up and extended directly from student thinking rather than the converse. This one element leads to added layer of complexity to teaching as suddenly all of the ideas in the classroom have to be surfaced and some subset of those ideas needs to be selected to talk about in public. Authentically listening to children’s ideas while leading a class with a specific objective and trying to move all of the students within that class toward that objective leads to complexity that most teaching does not contain — and so we call the teaching that requires this at its core to be Ambitious. The name of this kind of teaching is not a rhetorical device, it is a reminder that learning to teach is challenging.

Another added layer of complexity is that when ideas are shared or presented to the whole group, not only does a teacher need to be conscious of how their decisions in this theater impact every child, they need to make sure that whatever idea that is being discussed is clear for every child. In a mathematics classroom this can be done through use of thoughtful representation, asking clarifying questions, asking students to listen to and restate each others’ ideas, adding on explanations to the student explanations, etc… but all of these individual practices have the same goal — ensure that everyone understands what is being discussed while treating students as sense-makers.

Based on this photo (which has a portion of the strategy cut-off on the right hand side), what mathematical idea is being discussed here? How do you know?

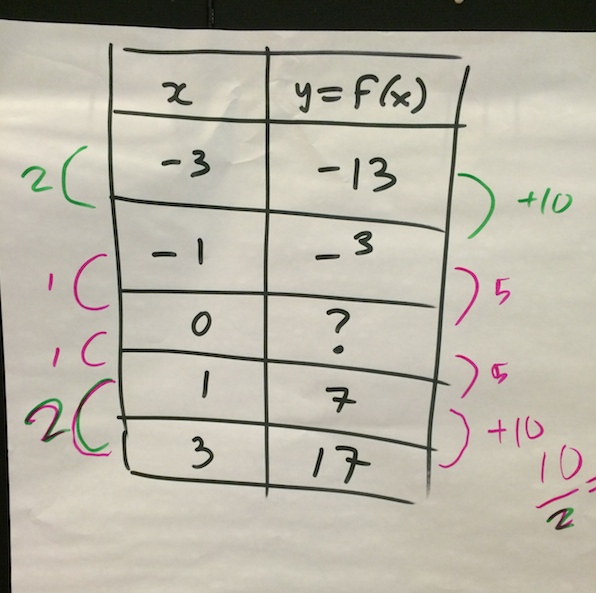

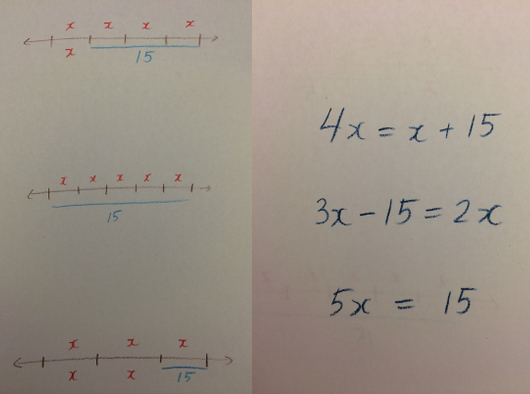

In order to make better choices about what problems and what representations of those problems to use, teachers need to develop specialized expertise about how students understand, and often misunderstand, their subject area in order to surface those important understandings and support students in transitioning to other understandings.

What mathematical ideas are being connected here? Why might that be helpful? What’s missing in these representations?

Now to be clear, I cannot easily describe Ambitious Teaching in a single blog post. Magdalene Lampert wrote an entire book about it and she only described this kind of teaching in the context of a single 5th grade mathematics classroom. All I can hope to do is to generate questions about teaching and to hopefully suggest that there is greater complexity to even typical teaching than the selection of the three worked examples for the day.

This entire short talk by Richard Feynman is worth watching, but if you look at his point at about 5 minutes into the video, you’ll hopefully understand my next point better.

[youtube id=”EYPapE-3FRw” parameters=”rel=0 start=300″]

Most of the time when we talk about teaching, we do in such vague terms that our conversations slide past each other. This includes educational research which claim to show that this method of teaching is better than this other method of teaching without carefully defining what the methods being compared actually are and what the goals of either particular style of teaching might be. One goal of my work this year is to make certain teaching practices explicit for teachers in our project so that when we talk about teaching we can be reasonably sure that everyone understands the decisions being made and why someone might make one decision or another based on the objectives of the teaching for the day.