In our project, we organized our work this past year around the use of instructional routines (née instructional activities) with teachers. Our curriculum work has been largely focused on instructional routines, our professional development activities have been focused on instructional routines, our school-based work in some cases has shifted to focus on supporting teams using instructional routines together. Our objective this last year has been to develop teachers in teaching ambitiously through the use of instructional routines that embody this kind of teaching.

Instructional [routines] are tasks enacted in classrooms that structure the relationship between the teacher and the students around content in ways that consistently maintain high expectations of student learning while adapting to the contingencies of particular instructional interactions.

Instructional routines are a little bit like a standard play in sports. If everyone knows the play, then the game runs more smoothly. But just like when in sports plays have to be adjusted due to what’s going on in the game, instructional routines have to be adjusted on the fly due to the ideas that emerge from students in the classroom.

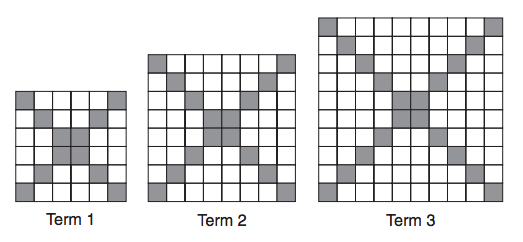

Here is an example of a task intended to be used in an instructional routine called Contemplate then Calculate.

Find the number of grey squares in the next term of this pattern.

The instructional routine Contemplate then Calculate has (roughly) these five steps:

1. Launch: The teacher launches the routine to let students know what, why, and how the class will be proceeding.

2. Noticings: The teacher flashes an images for kids and asks kids to describe what they noticed in the image, share this with a partner, and then records some noticings for the whole room to use.

3. Partner work: The teachers reshares the image with a problem task associated with it, then kids work with a partner to solve the problem given.

4. Share: Selected students share their strategy with the whole class while the teacher annotates the strategy and uses talk moves like restating and probing questions to ensure that everyone understands the ideas being presented.

5. Meta-reflection: Students write reflections based on choosing from prompts given to them by the teacher.

The high level goals of Contemplate then Calculate are to support students in surfacing and naming mathematical structure, more broadly in pausing to think about the mathematics present in a task before attempting a solution strategy, and even more broadly in learning from other students’ different strategies for solving the same problem. A critical aspect of this and other instructional routines is that they embody a routine in which one makes teaching decisions, rather than scripting out all of the work a teacher is to do with her students.

This year we noticed a number of benefits to using instructional routines that lead us to plan continuing using them next year as well.

1. Instructional routines allow teachers to communicate about classroom practice with each other using a common language and common understanding of what kinds of instructional strategies are being implemented.

Usually conversations about classroom practice are extremely difficult because each teacher’s context is so different and because teachers visit each other so infrequently. My experience suggests that these conversations often devolve from talking about specific decisions that were made and the rationales behind those decisions and into discussions about mathematical topics and what order they should be taught. With a common instructional routine, teachers’ conversations can shift to a more granular level of discussion since so much more of the context can be assumed.

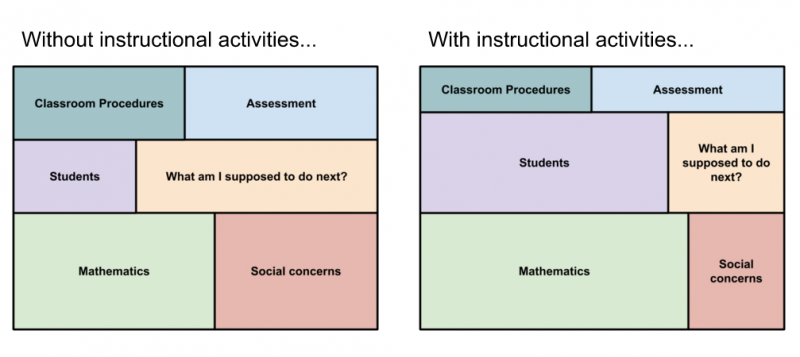

2. Instructional routines can support teachers and students in having access to high cognitive demand tasks by reducing the cognitive demand needed to attend to “what am I doing next”. Since the activity is routine and well-defined, the steps to doing the activity can fade into the background over time for both teachers and students. This allows more of the cognitive load for teachers and students to be potentially focused on making sense of each others’ reasoning and the mathematics of the task at hand.

Shifting cognitive demand for teachers and students

Teachers already have many routines they use in their classrooms but those routines may or may not be used by other teachers (see point #1) or they may have too many different routines that they enact for each type of mathematical task they use. In order for the cognitive benefits of an instructional routine to occur, the instructional routines must in fact become routine.

3. Instructional routines have allowed our curriculum team to rapidly develop mathematical tasks to fit into these instructional routines because we don’t need to communicate the routine separately for every task. The routine stays the same (but see point #4) over time while different tasks are enacted within the routine.

4. Since an instructional routine keeps much of the classroom interaction the same, it becomes possible for individual teachers or groups of teachers to iterate on their practice more rapidly. If every day a teacher has to re-invent her practice, then it becomes more difficult to figure out what teaching strategies work in her context, when those teaching strategies work, and why she might choose a different teaching strategy.

I remember my first year teaching. I was unprepared. I didn’t know how to structure lessons. Each day I was floundering. I kept experimenting and trying different activities, different ways of communicating with students, etc… I would have benefited from more support in planning lessons.Note that this benefit supports newer and experienced teachers differently. A new teacher needs a starting place to iterate on their practice from. An experienced teacher who wants to refine her practice needs a tool with which to do so.

5. In professional development settings, we and teachers in our project can model teaching strategies more easily (this is really a combination of point #1 and #4). Since the routine is well-established, when someone does something different within the routine when modeling it with a group of teachers, it becomes easier to focus on the something different.

For example, we used the routine Contemplate then Calculate to model instructional moves intended to facilitate student discussions. We then, as a group, unpacked just that aspect of the routine. This was enabled because instead of everyone participating having to keep all of the teaching occurring in one’s head at one time, the routine aspects of the teaching could be ignored to focus on the non-routine aspects for that day.

6. The instructional routines all include built in opportunities for formative assessment and responsive teaching. We struggled to find ways to staple formative assessment practices on top of existing teaching and mostly failed. Instead the different aspects of formative assessment (as described by Dylan Wiliam) are embedded within an instructional routines, which as it turns out, makes them easier to learn how to use.

There are other more mathematical benefits of these instructional routines, but those depend largely on the specific routine being used.

We intend to continue supporting the two instructional routines we used this year (Contemplate then Calculate and Connecting Representations) and to add one or two more routines to support different mathematical goals teachers may have, because we have seen each of the benefits of these routines listed above play out in various ways across our project.