I might post on this blog like I know what I’m talking about but each of these posts is a question really, an internal discussion that I share. I’m finding I have more questions than answers now.

The current model of education doesn’t work in my opinion, but I can’t see what should replace it.

The best models don’t look like they are very scalable, and would be difficult for the general public to even understand. The recent uproar in the Canadian media over the simple idea that we should value every child has certainly taught me that we need to do a lot of work educating the public about what we do.

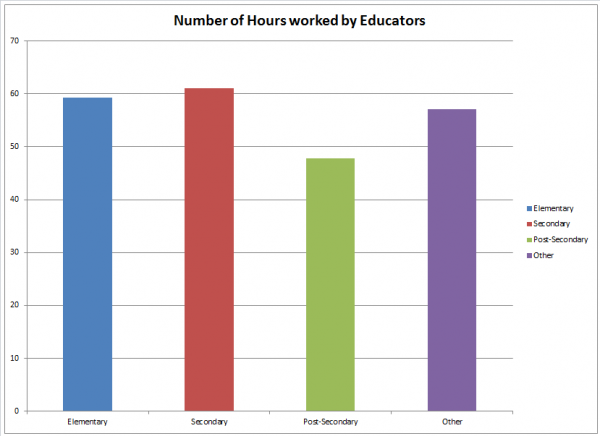

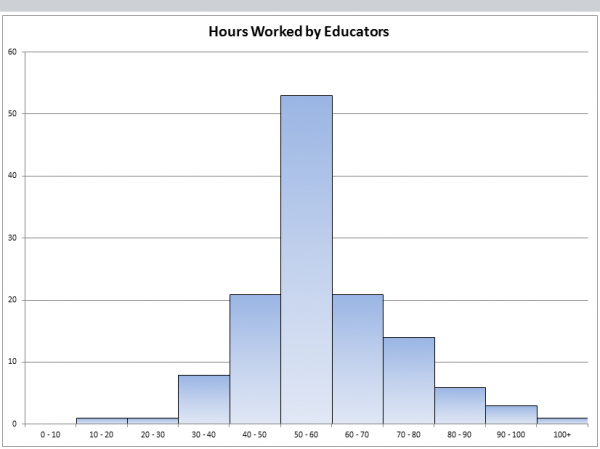

I like using technology in my teaching. It lets me do things and have my students construct meaning in ways that I never could have managed even a few years ago. I am worried however that generalizing what a few teachers do really well can be really damaging when diluted to the general teaching population. Introducing computers in most teachers classrooms leads to mass distraction in my opinion, especially given the lack of training that teachers have with them.

Formative assessment is good for example, and the best educators recognize that we should be assessing our students understanding informally all the time. Some schools have turned this into "thou shalt test and grade thy kids insessantly until their fingers bleed where they grasp their #2 HB pencils," and really damaging students. Using technology ineffectively can similarly turn into a gong show.

Worse, applying this use of technology to every school is incredibly expensive. There are 76.6 million people in some sort of school in the United States alone, if each of these people had a $500 laptop, that would cost the US about $40,000,000,000 to outfit each student, not including the cost of distribution, maintenance, and software which could potentially triple those costs. By comparison this article suggests that to end world hunger, it would cost $195 billion. Given a choice between using my fancy tools with my students, which I LOVE to do, and ending world hunger, even for a year, I’m going to choose the latter. Obviously it’s not that simple, but it gets you thinking, is it worth it?

I’ve read that people think that students should be taking online courses, or moving at their own pace through videos, but this model worries me. I’m worried because I’m beginning to feel more and more that the important parts of education happen between the lines of the curriculum. If students spend more of their time learning in physical isolation from each other, these moments will begin to disappear.

I’m also worried that this will become another way to fleece the public pocket as educational publishing companies move toward a rental model of content and that educators as a whole are not yet ready to embrace the open source movement. We might get locked into a proprietary model before the open content model has gained enough of a foothold. Why is this important? Given the deep philosophical divisions in our society, do you want someone else having even more control over what your children learn? It is a lot easier to delete an "inconvenient" moment in history when all of your information is in digital form. I’m not being paranoid, revisions to history happen all the time in public school textbooks.

Some have suggested that we need to refine the accountability model for education. If we just test the students more carefully, and then use this data to change how we hold teachers accountability, that this will drive educational improvement. Of course this model conveniently forgets the narrative that we’ve been testing our students more and more for the past 20 years and seeing a steady decrease in school quality at the same time. It also forgets that there is an extremely strong relationship between student test scores and their poverty level. Poverty is a result of poor education, is their claim, rather than an effect of a decrease in real earnings, or a widening gap between the rich and the disappearing middle class. The only benefit I can see, as these so called reformers spout their nonsense, is that they have helped crystalize my opposition to the use of standardized tests for high stakes purposes. How did these educators, and many of them are educators although some are not, get so far off track from student learning?

I also wonder about alternative education. I’ve been reading about homeschooling, unschooling, Montessori schools, Waldorf schools, and all sorts of interesting ways to educate people. I’ve read some of John Gatto’s work recently and beginning to wonder if I haven’t done a great deal of evil over the course of my career unwittingly. "Think like I do" I say, and help erode my student’s ability to think independently. How do I balance an obvious need of society for some structure with my belief that everyone needs to be capable of independent reasoning? Gatto has some strong arguments exposing some serious flaws with public schooling and reading them makes me feel uncomfortable.

A year from now I may look at what I’ve written here and think I’m being pretty foolish. Right now though I feel like I have a million questions and not enough time to answer all of them.