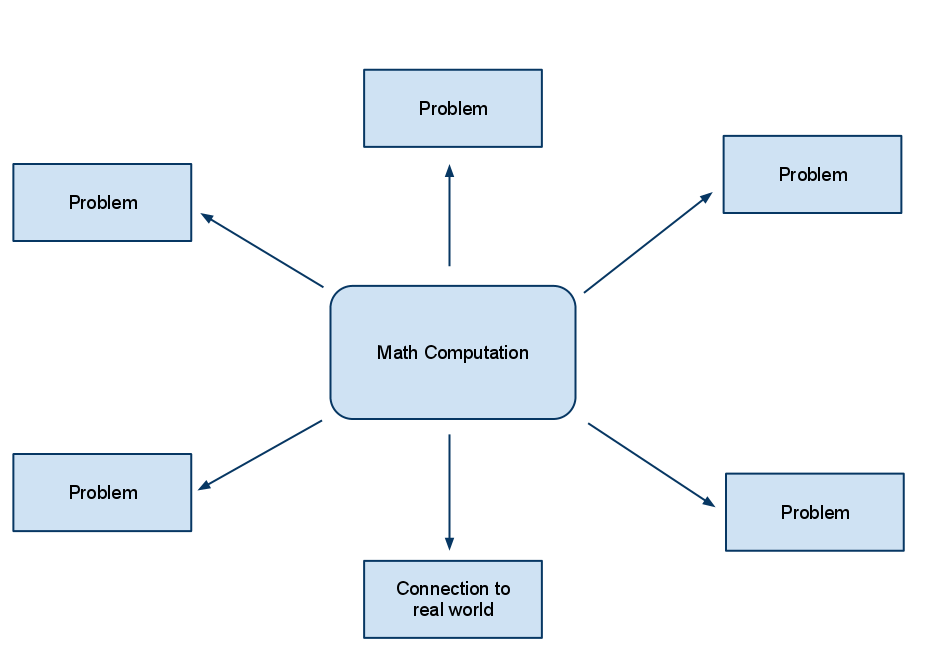

Here’s what math curriculum looks like in most schools.

The computations we want students to be able to do are chosen, and then we find problems that match these computations, and if we are able, we find some real life connections to the computations. Generally the real world connections are an after thought, and many times teachers are responsible for finding these connections when the textbook problems they are given are really examples of pseudo-context rather than a real connection. It can be difficult to attach real world context to the curriculum we are expected to teach and many times teachers aren’t able to do it.

There is a serious flaw in how this curriculum is constructed. The mathematics that is chosen has no motivation in the minds of the people learning it. If you have wondered why so many people hated mathematics class, it was because they couldn’t see the point of it. That’s because there was no point. People who hate mathematics were learning apparently meaningless algorithms for the sake of the algorithms themselves rather than for the processes in our world where the algorithms describe.

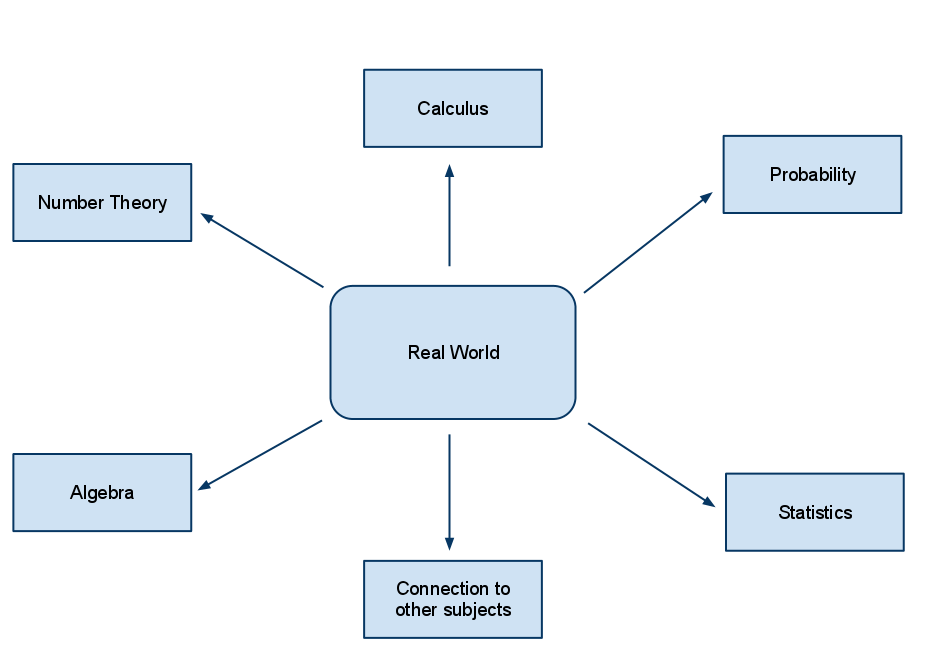

What if we flipped this process? What would happen if we changed the diagram so the real world problems were in the middle of the diagram, and we chose what mathematics to look at based directly on how it helped us understand the real world? The diagram would look like this:

I need to be careful here to define “real world.” I do not mean that students will spend their time learning how to solve the math problems that may arise in their life like an endless stream of super-market math. What I mean by “real world” is that the problems students would work on would have a shared context to which students will understand. This context might be a real problem that students or their teachers find, it might be part of an interesting challenge given to them by a mentor, or it might be simply exploring ‘what if’ in a puzzle.

The thing is, when you place context at the centre of the curriculum an immediate shift happens. Now the mathematics itself has immediate relevance, since the applications are focused on something which has meaning for the students. You also gain the ability to shift away from a computational focus (since that’s what should be for) and look at problem formulating and solving. Gone is pseudo-context. Gone is mathematics which has no relevance in the lives of our students.

Formulating the curriculum like this also makes finding connections to other areas where the students are studying much easier. Everyone can talk about the real world, and it can happen in every subject area. It becomes easier to turn our curriculum from caged subject areas into an open dialogue about life.

It also becomes easier to update the curriculum. The topics of a typical mathematics curriculum have changed very little in the past 100 years, and are nearly universal across the globe. However, in this curriculum the focus is on what is happening in real life, and it becomes easier to select what is important to teach as all of us experience the real world daily. In fact the curriculum itself could easily change from year to year and the actual mathematics that is taught could be different in each school. After all, what is important in mathematics is the process that students go through, not the end result.

There is also room in this model of curriculum for fairly advanced topics. You can see that calculus could be one of the branches of this type of curriculum since it deals intimately with understanding many complex phenomena in our world. If a student wants to extend themselves and get excited by the mathematics itself, we can still give them that opportunity. We can be more flexible in how we plan our lessons and give students more choice in how they approach problem solving.

What is not easy to represent in this diagram is what the arrows, which are common to all of the different possible branches of mathematics and their representation to the real world content. In my mind, these arrows represent part of the process of translating a real world problem into mathematics. Students have to know how to formulate problems, develop criteria for establishing what pieces of information they have are useful, and determine if their solution makes sense. Since they know for certain that the solution represents a real world phenomena, it will be easier to judge a correct solution from an obvious false one.

This shift also makes it easier to talk about the big ideas of mathematics. Most of the time we spend our classroom time so focused on the minutia that we forget that there are some powerful ideas in mathematics that are useful tools for thinking for students.

Here is a presentation to explain some of what this shift looks like for me.

Mathematics education has to change. I have spent my life either feeling defensive about my love of mathematics, or commiserating with people who agree with me. People say that they hate mathematics because they do not see how it is relevant. Let’s change mathematics curriculum so that context (which does not necessarily have to be “real world” but should be meaningful) is king.

Update: In my current work as a curriculum developer, I’ve been working on an alternative to the proposal above in our curriculum work which embeds contexts where they are meaningful but does not flip the arrangement as above. The key shift in our curriculum work is viewing students as sense-makers and fore-fronting student thinking as much as possible while still making mathematics accessible to all students (through shifts in instructional practices rather than shifts in the mathematics itself).