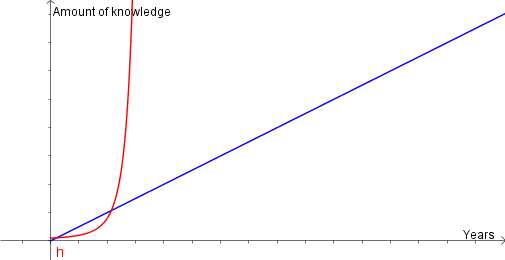

Here’s my observation. What we have students do during school does not at all resemble what they will do when they finish university. In fact there is literally no relationship at all, and our students can see that and of course, they rebel. I’ve talked about an alternate school structure before, this post is really an extension of that post.

The real life workplace does involve repetitive tasks (like school) but is also coupled with problem solving. Actually almost all of the interesting parts of anyone’s job are when one is required to problem solve or at least learn a new skill. We can actually be given some problems in the workplace which have no immediate solution, in fact they may have no perfect solution at all. Solving a problem in the workplace is extremely rewarding in itself and probably leads to greatest job satisfaction for most people. Failure, disappointment, success, creativity are all parts of the modern workplace.

School on the other hand involves very repetitive tasks, and very little creativity. Students are isolated from true failure through things like social promotion and minimum grade boundaries, disappointment is temporary, and the rewards for success on any one individual project are very small. One could argue that working hard all the way through school can lead to big rewards in the form of scholarships for entrance to university, but in terms of hours worked, this can actually be considered a fairly small reward. One of the only areas schools are like the workplace is that students get lots of opportunities to experience success. Unfortunately these individual events are often to contrived and unlike the real-world as to lack meaning.

So what if, as soon as kids had some basic skills (like reading, writing, simple arithmetic) under their belts, they were exposed to a more realistic school where students were involved in solving real life problems and their solutions (where appropriate) were actually implemented? There are lots of schools which implement this in various ways, and as long as the programs are structured appropriately, they seem to be successful. I’m thinking of automotive schools, culinary schools, etc…. for middle and high school students. So in other words, lots of schools actually do this already in various ways and are experiencing success. All I’m suggesting is that we expand these types of programs, especially into the academic areas.

Here are some examples off the top of my head.

Suppose, as part of learning about biology, students were involving in collecting and analyzing data from their local ecosystems. One of the great difficulties biologists have is in collecting enough worthwhile data from a wide enough variety of places to be useful. If students collected this data carefully and correctly, this could save an enormous amount of time for biologists and greatly expand the number of geographic environments that could be analyzed.

Students who need to learn about literature could collaboratively write a book (such a collection of short stories for kids), which they would be expected to market and sell themselves. They would learn valuable lessons about the importance of editing one’s work, the difficulty in getting work published, and how one can successfully complete a lengthy piece of writing. Obviously very similar ideas could be implemented by substituting book for movie, radio station, magazine, newspaper, etc…

Want students to practice their arithmetic? Have them work together to run a store (perhaps where the products created by the students themselves are sold?) and keep track of inventory, manage their budget, and run a cash register (perhaps without the technical assistance that makes this all too easy to do?).

I think that most areas of the curriculum could be turned into more job-like projects but there might be some areas which would not lend themselves well to being ‘job like’. Of course there are lots of other ways of approaching these topics which would be more meaningful and engaging for the students. Learning about some topics through formal debates (and the associated research skills), write letters as if one was participating in a historical event, these are a couple of ways to increase student involvement especially in the social sciences.

In order for this type of school to work, one would really need to take a careful look at the curriculum and ask yourself, what of this curriculum is vital for the students to know, and what of it is intended to be used as a vehicle to teach skills? Personally I think so much of what we teach is really irrelevant for students and could easily be trimmed down a fair bit. These kinds of schools would be great for encouraging depth of knowledge and specialization of individual students instead of the generic cookie-cutter model of education.

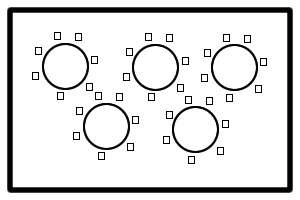

A typical classroom might look something like this. The problem with this arrangement that I see is that almost no one actually works under this arrangement. Why not? It’s distracting! this is similar to the layout in a lot of teacher staff rooms, and it is my experience that very little work happens in the staff room when it is full. There are too many people around and too many things to see and do.

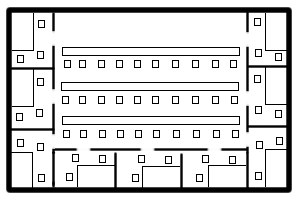

A typical classroom might look something like this. The problem with this arrangement that I see is that almost no one actually works under this arrangement. Why not? It’s distracting! this is similar to the layout in a lot of teacher staff rooms, and it is my experience that very little work happens in the staff room when it is full. There are too many people around and too many things to see and do. So I propose a different arrangement. Here’s a possible variation that might work. The big difference here is, students have their own workspace. They can work in their small groups with a few students working in the middle section, possibly under the guidance of the teacher. They have much fewer distractions available to them.

So I propose a different arrangement. Here’s a possible variation that might work. The big difference here is, students have their own workspace. They can work in their small groups with a few students working in the middle section, possibly under the guidance of the teacher. They have much fewer distractions available to them.