I have been involved in the professional development of teachers since 2006 and in that time, I have learned a lot about how to support teachers in their professional growth.

WHAT I USED TO DO

My very first presentation for teachers was a 45-minute workshop on Open Source Technology in Education. It was horrible. I talked for 45 minutes straight without taking or asking any questions or giving teachers a single example they could use in their classrooms. Two of my colleagues fell asleep.

But, I improved. The next year, I ran the same workshop in the school computer lab and gave teachers access to a bunch of programs they could use, then at the end of the workshop, I pointed out that all of these programs were free because they were part of the open source movement.

Neither of these two approaches leads to a significant change in teacher practice. In one case, I gave teachers a whole lot of why they might want to use a teaching tool without the how, and in the other case, teachers got a lot of how they can use the software, but with limited pedagogical approaches, and very minimal emphasis on why teachers might want to use open source tools. Teacher engagement was significantly higher with the second approach though…

WHAT I DO NOW

The structure of a workshop that I run now is quite different than what I used to do based on what I have learned, especially from Amy Lucenta and Grace Kelemanik. Here is what I do if I am lucky enough to be running a day-long workshop.

- I start with an overview of the objectives of the workshop and give teachers the agenda for the workshop. If I have enough time, I ask teachers to think about their own goals for the day, describe them to a partner, and then gather and record some responses from the room.

- Next, I give teachers a brief summary of why we are experiencing what will experience together and how it is helpful for students.

- I then engage teachers in a teaching and learning experience with teachers playing the role of students and myself playing the role of teacher. I try to make this experience as authentic as possible by encouraging teachers to stay in role and to think and speak like a student. If they think a student would do something, I ask them to be that student. If the goal for the workshop is to introduce an instructional routine and I have enough time, I model the instructional routine two or three times so that teachers can see what remains the same each time the routine is run and what changes based on the task and the student responses.

- We then unpack the experience together so that teachers can name the parts of the experience and describe how those parts are helpful for students.

- I give teachers get structured planning time at this stage so that they can look at some sample resources in more depth and make decisions about how they will use those resources. Usually, during this planning time, teachers work through some example mathematics using a planning template. While teachers work, I circulate around the room, both to see how they are planning together and to find some volunteers for the next part of the workshop.

- The most powerful part of the workshop is when teachers who have volunteered play the role of teachers in a rehearsal of the work experienced earlier. A rehearsal is very much like the original experience teachers had towards the beginning of the day, but during a rehearsal, we can pause the action, rewind if necessary, and experiment with different instructional moves. The goal of a rehearsal is to get every teacher considering teaching together not to evaluate and give feedback to individual teachers.

- I close the workshops with a reflection activity and gather further feedback from teachers, usually with a standardized online form or with index cards.

One important element of the day-long workshops is that they are aligned to the curriculum we have developed so that teachers have access to resources they can use to continue to implement the ideas they learn during the workshop routinely through-out the year.

WHAT DOES RESEARCH SAY?

Here are some key principles my colleagues at New Visions for Public Schools, Angel Zheng and Simran Soni, found when they looked at research on effective teacher professional development.

Professional development for teachers should:

- Be of sustained duration and focus. In particular, the research reviewed found that more than 14 hours of professional development had a positive and significant effect on student achievement, while those with less than 14 hours did not (Editorial note: This number of hours is probably an artifact of the specific studies included, the necessary duration probably depends on a variety of factors),

- Include a heavy focus on providing evidence-based research about the subject before providing specific strategies to address the content,

- Rooted in subject matter focused on the student as a learner to have the highest impact on student achievement,

- Include time for the teacher to interact with the procedure taught and practice how they would apply it in their own classrooms. This may include an emphasis on teachers experiencing the material as a learner, not an educator,

- Couple professional development opportunities with a new curriculum or pedagogical tool. Simply providing a new resource without any additional support does not work, it is necessary to provide resources with explicit support,

- Provide explicit resources to assist teachers in planning while others offered time for teachers to ask for support from them and from the other teachers.

According to Zheng and Soni (Internal Research Review, 2017), “a set of researchers (Yoon, Duncan, Lee, Scarloss, & Shapley, 2007) looked across 1,300 studies that address the impact of professional development. They then narrowed the studies down to nine that met What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) Standards. Across these nine studies, professional development for teachers increased their student achievement by 21 points (out of 100).”

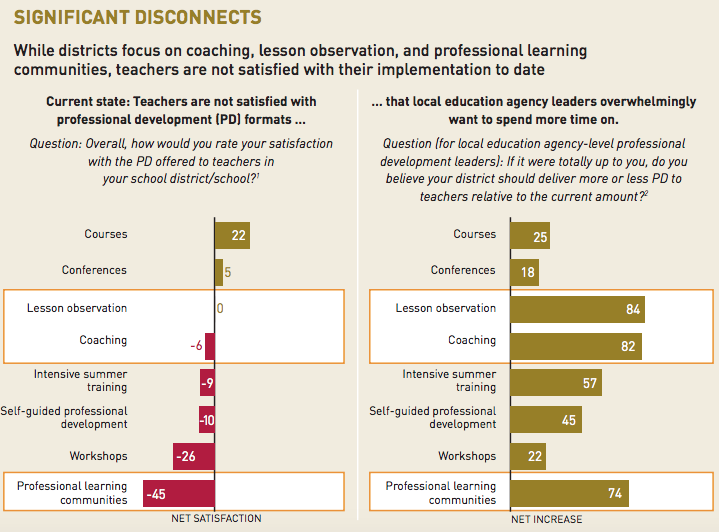

You can probably see that the professional development structure I typically use aligns well with the research. It also is very engaging for teachers who frequently report strong satisfaction with workshops that I and my colleagues run, which as it turns out, is rare in professional development. According to this survey on teacher professional development, workshops are only ranked slightly behind professional learning communities as teachers’ least favourite professional learning activity.

While I used to think good presentations were mostly about format and delivery, now I am convinced that the structure of the workshop and the infrastructure that exists to support the work teachers do after the workshop are the most critical elements for creating professional learning experiences that actually help teachers and consequently, their students.

What I would change

One area that is currently completely missing from my work with teachers is the ability to visit teachers before and after workshops to see the impact of the professional learning experiences I provide. Since the primary goal of the professional learning I support is to give teachers instructional tools they can use with their students, without a feedback mechanism that incorporates what they actually do with students, I feel sometimes like I am operating in the dark.