Research, by itself, rarely changes teacher practices. Presentations on why their practices should change rarely change teacher practices. Attending conferences rarely changes teacher practices (a teacher may adopt a few new things from a conference, but how often has a teacher come back from a conference and begun to teach in a completely new way?).

What does change teacher practice?

Eric Mazur, in his lecture "Confessions of a Converted Lecturer", recounts how standard measures told him his teaching style was sufficient, but when he applied a different measure, he was quite surprised to discover that his teaching had nearly no effect on his students’ conceptual learning of physics. The evidence that convinced Eric that his teaching needed improvement was the results of investigating his own teaching using a different tool, the force concept inventory. The key here is investigating his own teaching, not necessarily the tool he used.

In an essay titled, "How One Tutoring Experience Changed My Teaching", Sara Whitestone recounts how she discovered that the writer’s voice in their writing matters, and how she had to do more to help her students develop their own voices, rather than adopting the writing voice of their teacher. The tutoring experience is not what changed her teaching, it was her reflection on that tutoring experience that changed it, but the experience acted as a catalyst for this reflection.

When I asked the question, what evidence shifts teacher practices, on Twitter, I had a few responses, which could be summed up with these two tweets.

@geonz @davidwees Agreed. If anything persuades, it’s experience. Few truly change practices based on argument or fact #mathchat #edchat

— Ben Orlin (@benorlin) July 12, 2013

Why do teachers often ignore evidence? It is probably because the evidence they are presented is not grounded in their own experiences, but in narratives of experiences other people are describing. In other words, the way they are presented with the evidence is not supported by their experiences, and so they do not learn from it.

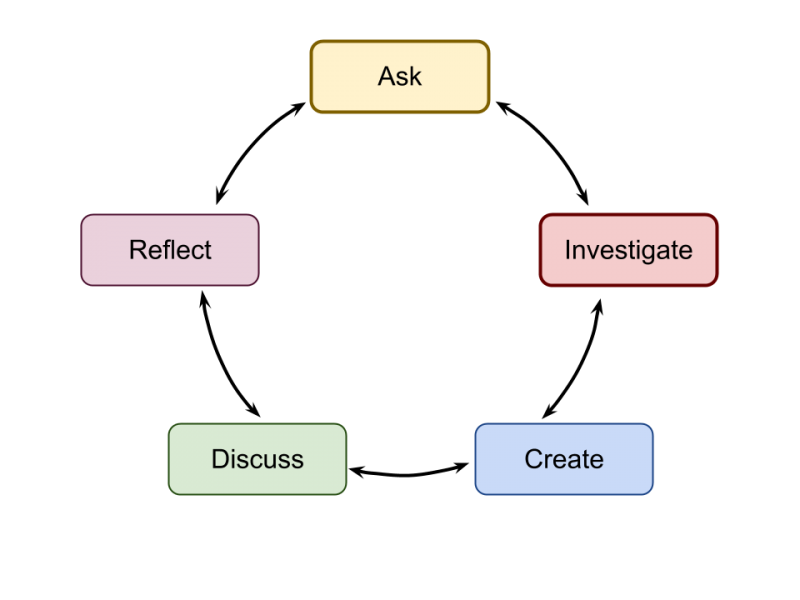

It seems therefore, that if we want teachers to change practices, one method which may work is to ask them investigate for themselves what their practices are, and participate in an inquiry into their own teaching practices.

What are some ways that you know are effective in promoting teacher growth and change of practices?

Anonymous says:

I think doing lesson study with teachers has been a great influence in shifting teachers practice. It incorporates all the ideas you mention above (experience, collect evidence around student learning, and reflection). I think the one thing it adds that typically action research does not is collaboration which can be valuable support tool when taking risks.

July 14, 2013 — 8:47 am

Zack Patterson says:

“Why do teachers often ignore evidence? It is probably because the evidence they are presented is not grounded in their own experiences…” Exactly. That’s profound, and extendable to manipulating any human behavior…it has to be made personal. To add, I think that for a teacher to change practices, the experiences of an initial or attempted change have to be positive ones…and a shared positive experience is even more powerful. This allows the reflection to shift more from yourself to the actual practices and makes the reflection process more objective. As for trying to initiate a change in another teacher, I think the lesson study (previous comment) is a good idea, but of you are trying to change in-the-classroom instructional practices, I think that the teacher needs to SEE it…experience it. Personally, a colleague and I gave up our planning periods last year to team teach. I learned more from watching his class, him watching mine, and the collaborative, motivating discussions that followed than any conference I’ve attended.

July 14, 2013 — 11:20 am

Chris McKenzie says:

It really is a constructivist experience, isn’t it? Which makes sense because we, as teachers, learn through many of the same methods that our students do. We want the students to have experiences that are more authentic because those tend to be more meaningful, so why not do the same for teachers?

July 16, 2013 — 10:41 am

David Wees says:

Absolutely, that is exactly my point. Teacher motivation and needs may be different than that of children, but the kinds of learning structures which are good for children are good for teachers.

July 16, 2013 — 12:18 pm

Brad Ovenell-Carter says:

@geonz might have hit it in his/her tweet. If we ask, “What evidence…” We’re presuming that teachers are looking for evidence. Chip Heath, in his book, Switch, suggests there are two sorts of people: those who respond to reason (evidence) and those who respond to emotional appeal. Teachers any be the latter. Heath also talks about the importance of environment or context. If that doesn’t facilitate change, those appeals may be for naught.

July 18, 2013 — 8:44 am

David Wees says:

Isn’t emotional appeal a kind of evidence? It’s not an evidence rooted in data, or in quantitative research, but it is a type of evidence that our minds (not just some teachers) accept?

July 18, 2013 — 12:21 pm

Alison Hutt says:

What stood out for me in your post is the idea of focusing on the needs of your students as the source for the development of curriculum and instruction–assessing the effect of what you are doing and having students do to determine the effectiveness of your program–as opposed to listening to what everyone else is telling you to do as a teacher. With new standards, new Common Core, new instructional strategies being flown constantly, it is easy to get wrapped up in what everyone else tells you that you should be doing as a teacher. Instead, my job should be to thoughtfully assess student learning, and then using these things as resources and tools to address needs as they are revealed. Thank you for this paradigm shift as I am preparing for my classes next Fall. This is huge.

July 25, 2013 — 11:09 am

David Wees says:

And there may be some overlap in what you do and what people recommend that you do, but if you use formative assessment to learn what you can about what your students can do, and then figure out what they know (and don’t know) from what they can do, then you are in a position to use your professional judgement to think about how to improve their understanding. You also improve your understanding of teaching from this type of activity, which will hopefully lead to fewer student misconceptions the next time around.

It’s also important to keep learning more about your subject area to ensure that you do not have any misconceptions. I know I discovered misconceptions I had in math many times during my career.

July 26, 2013 — 7:52 am