For the last two years, the project I am currently working with has been asking teachers in many different schools to use common initial and final assessment tasks. The tasks themselves have been drawn from the library of MARS tasks available through the Math Shell project, as well as other very similar tasks curated by the Silicon Valley Math Initiative.

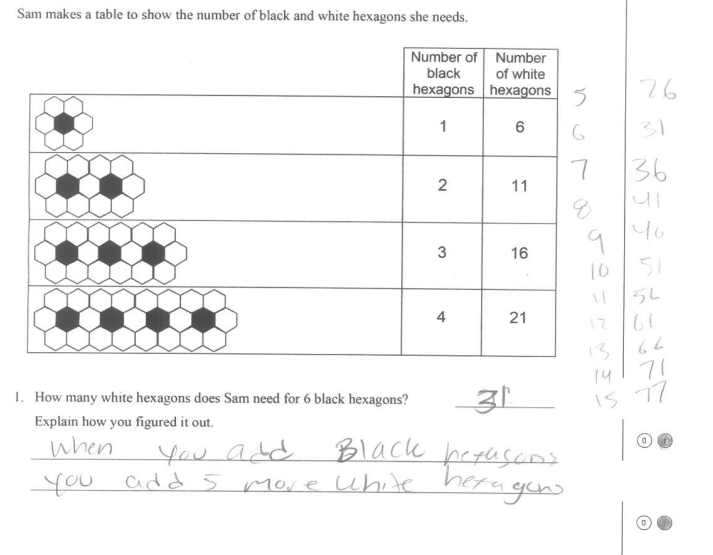

Here is a sample question from a MARS task with an actual student response. The shaded in circles below represent the scoring decisions made by the teacher who scored this task.

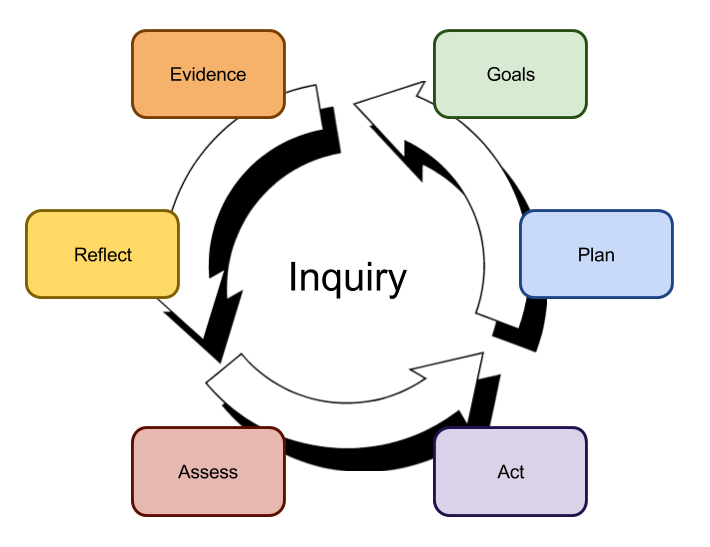

This summer I have been tasked with rethinking how we use our common beginning of unit formative assessments in our project. The purposes of our common assessments are to:

- provide teachers with information so they use it to help plan,

- provide students with rich mathematics tasks to introduce them to the mathematics for that unit,

- provide our program staff with information on the aggregate needs of students in the project.

We recently had the senior advisors to our project give us some feedback, and much of the feedback around our assessment model fell right in line with feedback we got from teachers through-out the year; the information the teachers were getting wasn’t very useful, and the tasks were often too hard for students, particularly at the beginning of the unit.

The first thing we are considering is providing more options for initial tasks for teachers to use, rather than specifying a particular assessment task for each unit (although for the early units, this may be less necessary). This, along with some guidance as to the emphases for each task and unit, may help teachers choose tasks which provide more access to more of their students.

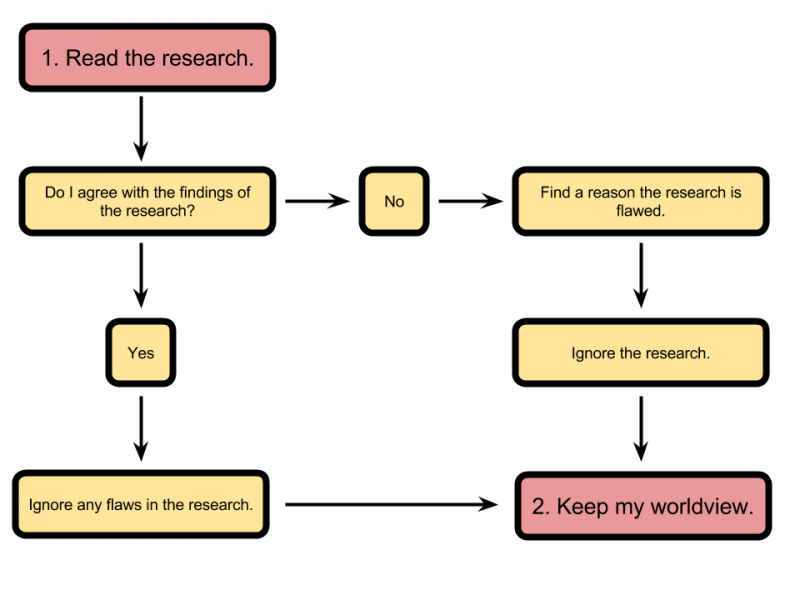

The next thing we are exploring is using a completely different scoring system. In the past, teachers went through the assessment for each student, and according to a rubric, assigned a point value (usually 0, 1, or 2) to each scoring decision, and then totaled these for each student to produce a score on the assessment. The main problem with this scoring system is that it tends to focus teachers on what students got right or wrong, and not what they did to attempt to solve the problem. Both focii have some use when deciding what to do next with students, but the first operates from a deficit model (what did they do wrong) and the second operates from a building-on-strengths (what do they know how to do) model.

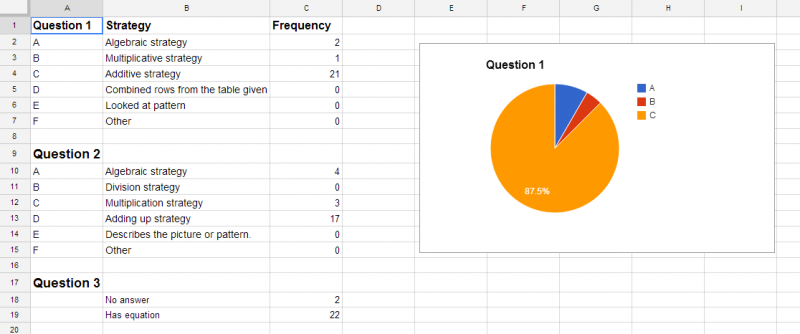

I took a look at a sample of 30 students’ work on this task, and decided that I could roughly group each students’ solution for each question under the categories of “algebraic”, “division”, “multiplication”, “addition”, and “other” strategy. I then took two sample classrooms of students and analyzed each students’ work on each question, categorizing according to the above set of strategies. It was pretty clear to me that in one classroom the students were attempting to use addition more often than in the other, and were struggling to successfully use arithmetic to solve the problems, whereas in the other class, most students had very few issues with arithmetic. I then recorded this information in a spreadsheet, along with the student answers, and generated some summaries of the distribution of strategies attempted as shown below.

One assumption I made when even thinking about categorizing student strategies instead of scoring them for accuracy is that students will likely use the strategy to solve a problem which seems most appropriate to them, and that by extension, if they do not use a more efficient or more accurate strategy, it is because they don’t really understand why it works. In both of these classrooms, students tended to use addition to solve the first problem, but in one classroom virtually no students ever used anything beyond addition to solve any of the problems, and in the other classroom, students used more sophisticated multiplication strategies, and a few students even used algebraic approaches.

I tested this approach with two of my colleagues, who are also mathematics instructional specialists, and after categorizing the student responses, they both were able to come up with ideas on how they might approach the upcoming unit based on the student responses, and did not find the amount of time to categorize the responses to be much different than it would have been if they were scoring the responses.

I’d love some feedback on this process before we try and implement it in the 32 schools in our project next year. Has anyone focused on categorizing or summarizing student types of student responses on an assessment task in this way before? Does this process seem like it would be useful for you as a teacher? Do you have any questions about this approach?