Thanks to @rmbyrne and his Free Technology for Teachers website, I just saw Annie Lenox’s "The Story of Bottled Water" video which is recommended viewing, but chances are those of you coming to this blog know the story she’s telling already.

In the video, she talks about the process of manufacturing demand, in which a company uses advertising to turn something people don’t need, into something they do. I thought about what she said, and agreed that I myself own many things that I almost certainly do not need. I also thought of the parallel process that is happening in the United States.

Right now educators, parents, and students are being sold a myth of an education system in crisis. By all standards, nothing has changed in education in 40 years across the US, so why is everyone in so much of a panic to change the system? While no one can claim that the US public education system is perfect or isn’t in serious need of improvement, to imply that we should be in a state of panic is at best irrational. When people panic, they will grab at any solution which seems plausible. The US public are being sold a lie, a false-hood, and the solution to the problem all at once.

The US President’s state of the union was fairly uninteresting according to accounts I’ve read because he really said nothing new on education. I didn’t watch it, but he had a pretty simple mesage according to the commentaries I’ve read. "We must do better because we are being beaten. We must do better because the American school children do better." Attached to this message is Race to the Top which encourages charter schools, teacher accountability through standardized testing, and national curriculum standards.

The question you should ask is, if I wanted to change the US education system to be more privatized, how could I convince the US public that this is necessary? Oh right, we’ll just do what we did with the Gulf War, we’ll manufacture a reason why there is a problem, and then provide the solution at the same time, and imply that the only solution lies with greater accountability of teachers.

By implying that teachers are the problem, the US DOE has managed to drive a wedge between teachers and their long time supporters, the parents of the kids they have in their classroom. "Can we trust this teacher," a parent will think, "or are they just trying to save their job?" While fortunately most parents seem to continue to be satisfied with their schools, it is only a matter of time before their (the reformers trying to change the system) message gets through. "American public schools are in trouble and we know the solution."

I don’t see the US system as being entirely in crisis. What I see is a lot of dedicated individuals who are working in a system for a world which needs transformation. I see a lot of educators who like what they do, and would be happy to work differently, but are trapped by the imposed bureacracy around them. I see a system which is failing a lot of students because of its lack of flexibility and inability of US politicians to solve the problem of poverty within their own country.

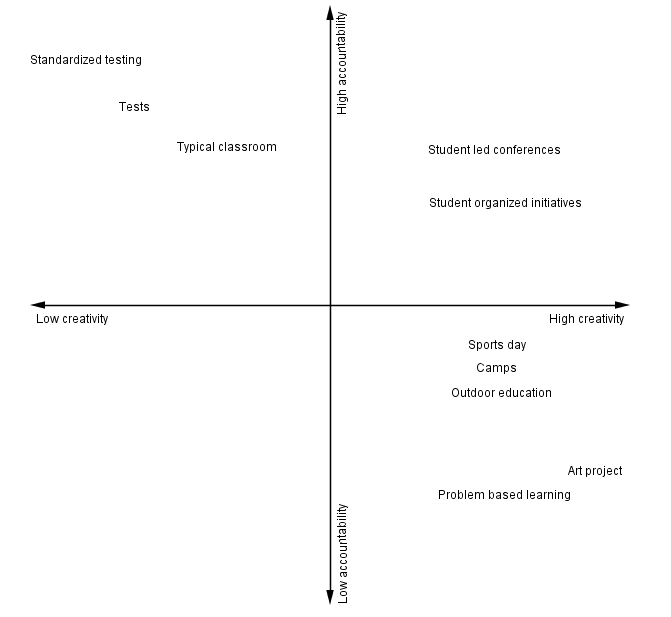

Instead of the greater accountability movement being pushed on US public education, schools actually need more freedom to pursue an education for children which would actually work. If we think about Zoe Weil, and her work for an education system dedicate toward building a more humane society, we might wonder where that would fit in our current educational model. Could it fit within the greater accountability model? Or would we need to rethink schools completely?

What is it about these people that make them think they can bamboozle the US public so completely? Oh right, because they’ve done it before.

Update: Just so people don’t think I’m making this up, check out this post about how little data these decisins are based on.