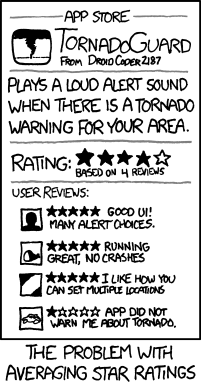

Every form of assessment of learning has bias. This bias may be hidden, or it may be quite obvious. As Cathy O’Neil points out, assessment is a proxy for what we want to measure – learning. We cannot measure the building of connections between neurons that is happening in the brain directly (or even potentially understand what that growth even means) so we use a proxy in the form of an assessment of the externally visible signs of learning.

One bias therefore is our tendency to forget that we are not actually measuring learning, we are measuring a proxy for learning.

Another bias is the language we use to do the assessment, whatever form that language takes. Language is necessarily a construct of our minds and no matter the appearance, it has deeply personal meaning based on our own experiences. As such, our use of language to communicate an assessment to a student contains an inherent bias based on our understanding of the language we have used.

The medium of the assessment also introduces bias. An assessment done on paper on pencil is limited to what can be collected in this form. As Dan Meyer and Dave Major are showing, digital assessments have different affordances (and different biases) that can change how students can interact with the assessment. Students who share their understanding verbally may have a very different explanation than if they write down their explanation.

There is further bias in the assessment based on our interpretation of the results of the assessment. If one knows the names (or race) of the people doing the assessment, is one sometimes more or less lenient? Look at this video of people assessing whether or not someone is stealing a bicycle. Do they exhibit any bias? Is it possible that teachers may experience similar bias (hopefully to a lesser degree!) when examining student work? How much of a difference to the student’s marks does it make if the work is messy or neat?

There are no doubt other biases in our assessments that I have not mentioned.

To combat bias, we must be first aware that it exists, and next that we should look at our assessments and ask ourselves, what bias is likely to exist in this form of this assessment? Can I address this bias? If not, can I use a second assessment in a different form and compare results?