Here are some tools which I’ve either used (or explored) for mathematics education. They aren’t all open source, but they are all extremely useful, and they are all free to use (free as in free beer, some of them are also free as in free speech).

Geogebra

This program lets you explore algebra and geometry, much like it’s proprietary cousin, Geometer’s Sketchpad. Having used both, I actually prefer Geogebra because I find it to be more flexible and easier to use. It will run on many different platforms including Windows, Mac, Linux, Android, and iOS.

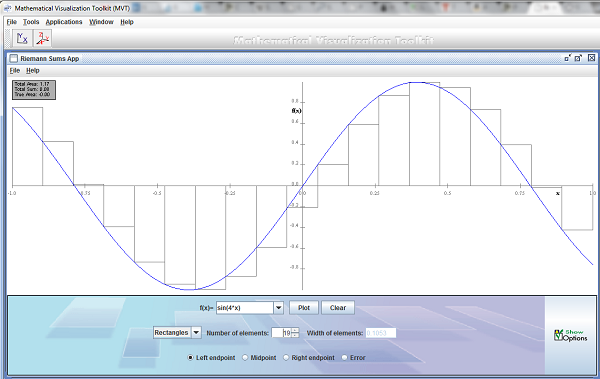

Mathematics Visualization Toolkit

The Mathematics Visualization Toolkit is exactly that, a program which lets you visualize mathematics. You can use it to build complex visualizations, or you can use the visualizations which are already included (which are awesome by themselves). You can either use the web start version of the toolkit, or download an offline installer.

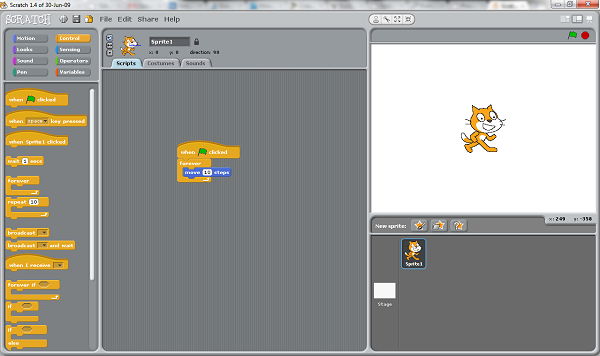

Scratch

Scratch is an excellent program for learning programming but also mathematics like variables, sequences, Cartesian coordinates, and other useful mathematical concepts. Developed at MIT, it is a free download and includes a strong user community to seek help, and see what else can be done with the program.

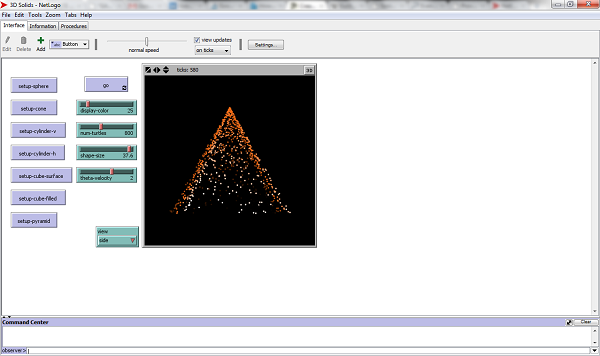

Netlogo

Netlogo is “a multi-agent programming modelling environment” (According to the Netlogo website). It comes with hundreds of models for all areas of science and mathematics preprogrammed. It is a free download and will work on any computer which has Java 5 or later installed.

Audacity

Audacity is an open source audio editor and recorder. One example use in mathematics is to record a bouncing ball, and use the visual data from audacities recording to turn this into a graph of bounce versus time between bounces. You can also use it so students can record 60 second podcasts explaining some aspect of mathematics.

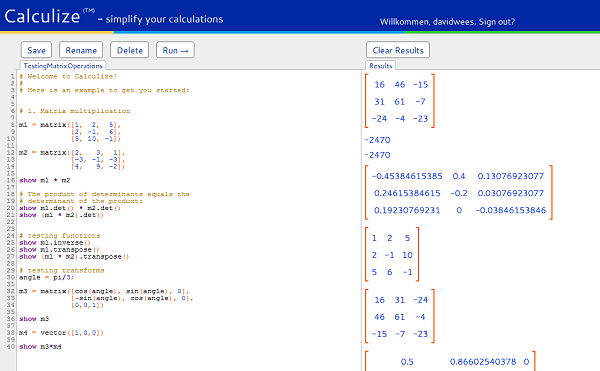

Calculize

Calculize is a free (currently) web app which lets students perform mathematical computations using a reasonably simple programming language.

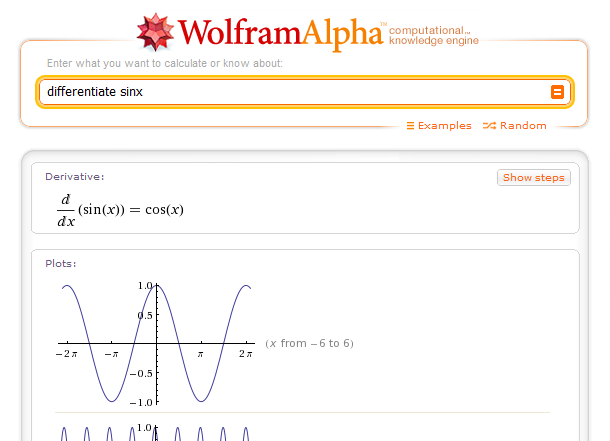

Wolfram Alpha

Wolfram Alpha is a computational engine built on top of the Mathematica architecture. It is amazingly powerful, and turns some homework assignments into a breeze. Recommendation: change your homework assignments, or do away with them all together.

Desmos

This is a free online graphing calculator. It emulates a lot of the functionality of a typical graphing calculator but with a much easier to follow user interface and without much of the non-graphing functionality of a graphing calculator. It is easy to create graphs, and then share those graphs with other people. It is also currently in development, so it is still improving over time with new features being added every couple of months.

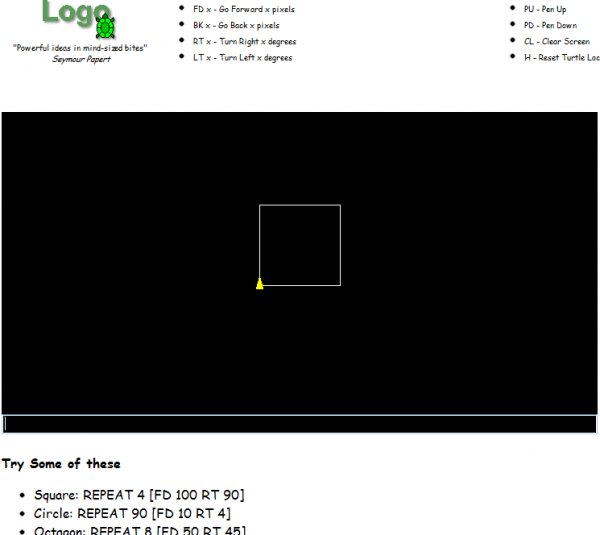

Logo

This Logo emulator lets students play with the classic programming environment Logo, built for kids by Seymour Papert and his colleagues at MIT, all online. It requires Java, but should run on most computers (sorry, no iPads…).

Google Earth

Google Earth is free (but proprietary) software that allows students to explore the world in 3d. One could use it for GIS applications, or even to explore the relationship between our 2d mapping system (longitude/latitude) and 3d space.

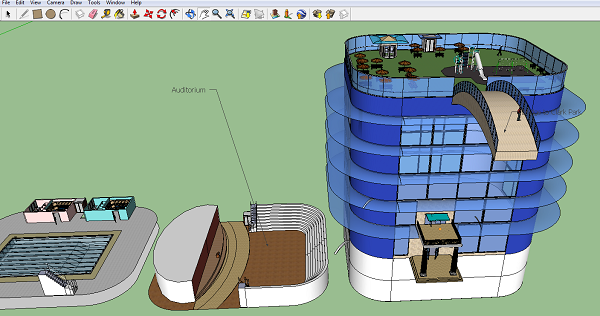

Google Sketchup

Google Sketchup (another free, but proprietary program) that allows students to create highly complex (or very simple, if they prefer) models. I’ve used it to have students construct their “ideal” school, and then from this model, they calculate the cost to build their school.

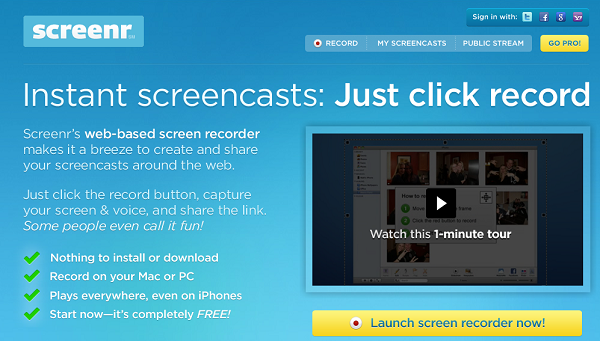

Screenr

Screenr is a free (for up to 5 minute recordings) screen-casting (think record your screen as a video) software. Some possible uses of it are for students to use it to create video tutorials, record their process of solving a problem, or create their own video word problems. Another alternative for screen-casting is Jing, but it publishes to a format which is harder to share in the free version.

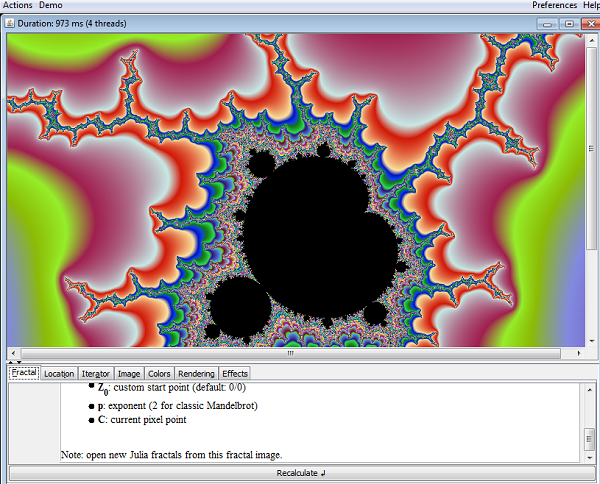

Endlos

Endlos is an open source fractal generator which I’ve found runs very fast. It runs in Java, so it should run on any computer capable of supporting Java. The ability to experiment with, and explore fractals is a very interesting thing for students to do, but very tedious to do by hand…

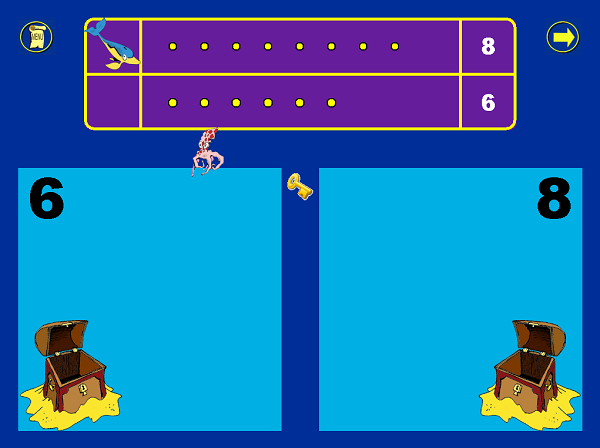

The Number Race

The Number Race is an open source program intended to help students who have dyscalculia develop their number sense. It has many levels of difficulty, and runs in Java, which means it should run on a wide variety of computers.

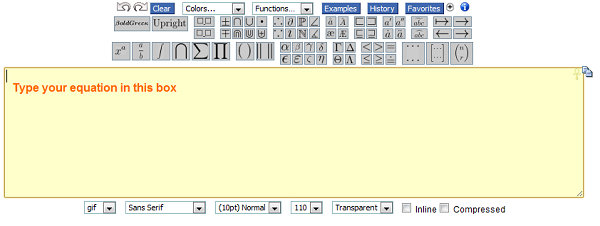

Code Cogs equation editor

This free to use online equation editor could be a nice way for students (and teachers potentially) to construct equation images for use in a website.

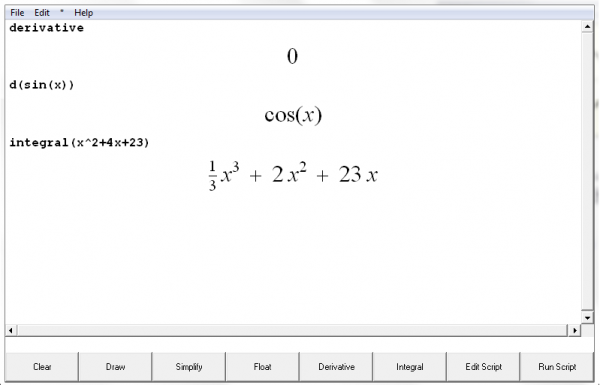

Eigenmath

Eigenmath is an open source program for symbolic manipulation in math. It runs either in Windows or on a Mac. Some examples of what it can do are shown above.

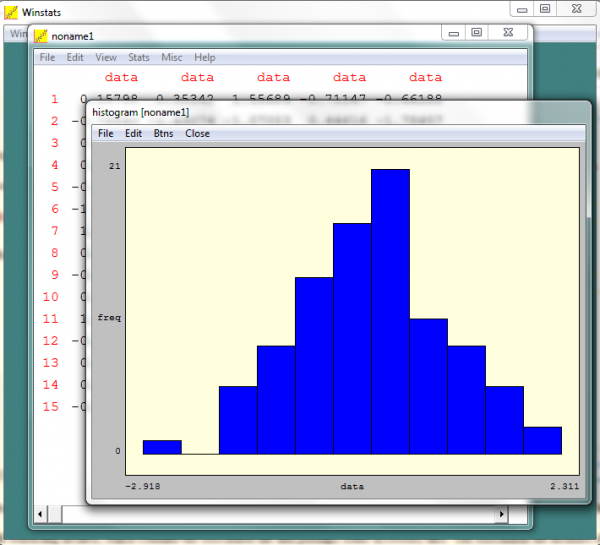

Peanut math programs

These 9 free programs cover a wide range of different types of mathematics. Above is the popular statistics calculation and visualization program included in the package.

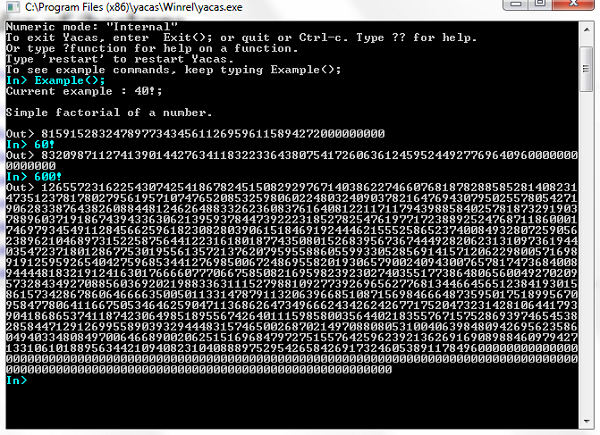

Yacas

Yacas (Yet Another Computer Algebra System) is a command line program which allows for the symbolic manipulation and calculation of mathematical expressions. One thing I like about it is that it calculated 600! in a fraction of a second, so it is very fast (an aside, ever wondered what 6000! factorial is?)

Free CAS programs

Update: Just found an open source implementation of LOGO (as described in Seymour Papert’s Mindstorms) here: http://www.softronix.com/logo.html

Other free programs which I have used either for constructing mathematical diagrams/simulations or with students in some way include:

The Gimp, Programmer’s Notepad, Flex Builder (free with an education license), Open Simulator, VLC PLayer,

Wolfram Demonstrations (requires a free browser plugin), and Project Euler.

You might find these programs as useful alternatives to the “free apps” which “help” students memorize formulas & algorithms. For an enormous list of other free programs see this helpful list.

What other free programs for mathematics education do you use with or for your students?