Unless you have been living under a rock, you have heard about a surge of people using artificial intelligence in art and writing to algorithmically produce original art work and original writing. Basically, people open up one of these services, enter in a prompt and set some inputs for the art work or the writing, and the system “magically” behind the scenes delivers the new art work or the new writing sample.

There are lots of moral questions that these services surface (E.g. Who owns the intellectual property that results from art work derived from analyzing an artist’s work?) but I’m currently concerned about the information is provided by these services. To understand my concern, one must first understand how these services work.

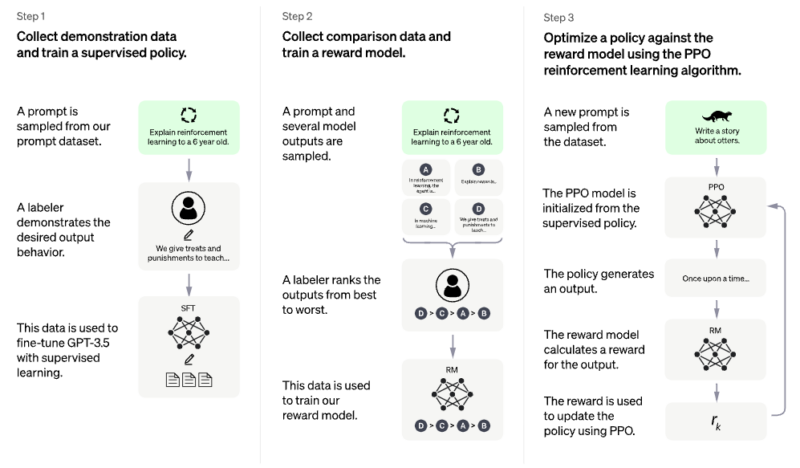

There’s a lot happening behind the scenes here that is worth knowing about in order to understand how these services work. Essentially, a set of training data is fed into an algorithm, which uses statistics to analyze the training data and determine the most important features of the training data set. The actual process is more complicated but, crucially, relies on an external source of information from which the algorithms derive insight.

I used ChatGPT to generate answers to some common questions in education that a student-teacher might have. The results were both impressive and worrying.

The results were impressive because this algorithm took relatively complex questions and generated realistic answers to these questions. The results are worrying because each of these answers is woefully incomplete in some critical way. Someone using this system as their sole mechanism to understand education will be left with a limited understanding of how education works.

Here are some responses to some questions about teaching. Let’s look at a couple of responses regarding learning styles.

What are learning styles?

Learning styles are different approaches or ways in which individuals understand and retain new information. Commonly recognized learning styles include:

- Visual: learning through seeing, e.g. diagrams, videos, and graphs.

- Auditory: learning through hearing, e.g. lectures and discussions.

- Kinesthetic: learning through physical experience and movement, e.g. hands-on activities and experiments.

- Reading/Writing: learning through reading and writing, e.g. texts and notes.

It’s important to note that individuals may have a dominant learning style, but often use a combination of styles in their learning process.

Are learning styles useful in teaching?

Yes, learning styles can be useful in teaching as they provide a framework for understanding individual differences in the way students process and retain information. By taking into account the learning styles of their students, teachers can tailor their instruction and presentation of material to reach a wider range of learners.

However, it’s important to note that the concept of learning styles is not universally accepted in the educational community, and some researchers argue that it’s not a useful or accurate way to categorize learners. Thus, it should not be used as the sole basis for instructional decisions, but rather as one of many factors to consider when designing lessons and assessments.

Generated using CHATGPT.

90% of educators believe that one’s pedagogical style should match the learning styles of students. However, there is no evidence that students learn better according to their learning style. There is evidence, on the other hand, that matching content to a mode of instruction (mostly visual, mostly audio, mostly kinesthetic, mostly reading/writing) matters. This latter point should be obvious — one cannot effectively learn how to dance from a book.

If this idea of learning styles is false, why does ChatGPT present it as true? The answer comes from how ChatGPT generates its responses. Recall that these systems rely on external data sources to create their generated responses. If these external sources of data contain bias or have a commonly accepted truth that is actually false, the output will contain these bias and falsehoods.

I’m not yet concerned that these artificial systems are ready to take over the jobs of teachers. I’m worried that policy makers will think that artificial intelligence is ready for education. I’m worried that students will use these systems to do their writing for them and fail to be exposed to more nuanced perspectives. As Henri Picciotto so eloquently says, “There is no one way” but ChatGPT currently produces a single not-quite-right answer.