“Your workshop was so interesting. I learned so much!” ~ An actual comment from a participant in one of my workshops yesterday.

Too often we ask teachers to listen for an hour or even two to someone talk nearly non-stop about what they know with perhaps a question thrown in once in a while. Since very few people can talk in an engaging way for this amount of time, it’s no wonder that so many people check out of this kind of experience.

But this experience is even worse because most educators have the background experience to engage in the ideas being discussed almost immediately but lecturing at teachers does not take into account their prior experiences. If someone lectures at teachers for an hour, I assume that they actually do not understand their topic or teaching well enough to think through how someone might engage in the topic more directly (the only exceptions are a keynote or a class size that numbers in the hundreds, very little else is possible without technology).

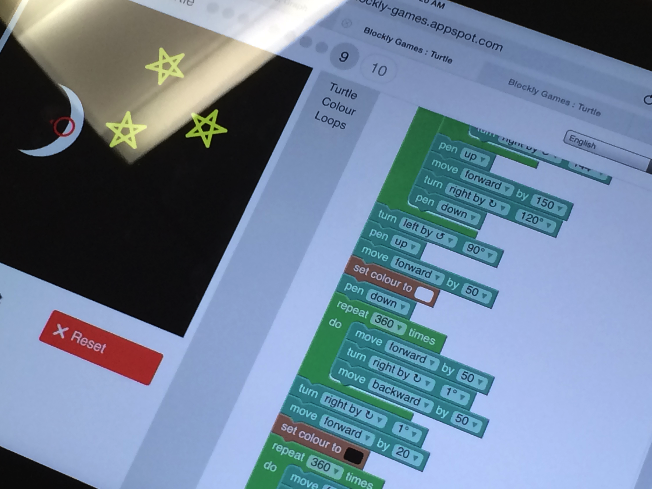

Yesterday I gave teachers a very brief introduction to one of four potential technology tools they might want to explore, and then I gave them access to the resources they would need to explore the tools. While they did this, I circulated around the room. Once it looked like they had made a decision about which tool they intended to explore more deeply, I asked them to group up with people exploring the same tool.

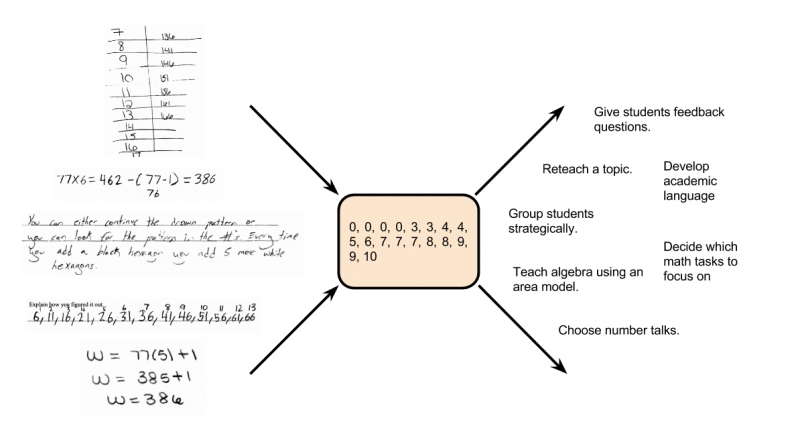

Then I continued to circulate around the room and made a note who seemed comfortable with the technology, who needed support, and who was vocal and who was not. I checked out who attempted to make things with the tools for themselves and who seemed more content to explore things already created. I used the information I gathered to decide when to pause the various groups’ discussion and work and how to structure the ensuing conversation and what questions might be useful to ask. I used the experiences the teachers were developing from the technology to inform the rest of the session.

A program written by a participant

I asked teachers to try and fill in a lesson plan template and choose a goal. Most did not, and so I decided to model a potential use of the technology using a Noticing and Wondering protocol. We then discussed what goal this activity might support and what this activity would look like if we tried to use pencil and paper.

At no point did I treat the teachers like they were incapable of figuring out how to use the technology themselves or thinking through for themselves how the technology might support their teaching. I certainly gave them opportunities for feedback on their ideas and offered them support when they seemed to need it, but I treated them as people who think and the ideas they had as being important to surface.

After all, this is all just good teaching, and don’t educators deserve that?