There is an article in Telegraph newspaper, shared with me by @bucharesttutor which suggests that people are born bad at mathematics. While this may be true, the research cited by the article cannot be used to make this claim.

From the article:

The research, led by Dr Melissa Libertus, focuses for the first time on children too young to have had lessons in maths.

Dr Libertus said: "Our study shows the link between ‘number sense’ and maths ability is already present before the beginning of formal math instruction.

"The relationship between ‘number sense’ and maths ability is important and intriguing.

"Maths ability has been thought to be highly dependent on culture and language and takes many years to learn.

"A link between the two is surprising and raises many important questions and issues."

During the study, 200 four-year-olds underwent several tests.

The problem with this article is that it makes the claim that this means that the ability to do math could be inborn. In fact, the article goes on to claim:

According to the research team, this means that being good at maths could be inborn.

There is a serious flaw in this research. By the time the kids are 4 years old, they may not have had any formal math instruction, but they have had lots of informal math instruction, from their parents and other adults in their lives. It’s possible that this is accounted for in the research, but it is not mentioned at all in the article. Articles like this make me upset because they are intended to be sensationalist, rather than really informative.

My son and I play numerical games. We play Go Fish, and roll dice as part of board games. We count everything. We count in 2s and 5s and 10s. We play with blocks and build intricate patterns. We talk about fractions, and split halves into halves to get quarters, add up halves to get wholes.

We play a game that @JohnTSpencer suggested which we call "How can we get ____?". I choose a number, and my son tries to figure out a bunch of different ways to get that number through addition. For example, I’ll ask my son, "How can we get 7?" He responds with, "Uh… (thinking) … 1 and 2 and 2 and 1 and 1 is 7!" I’ll ask him, "What are some other ways to get 7?" He’ll come back with, "Uh… (more thinking) … 1 and 1 and 1 and 1 and 1 and 1 and 1 makes 7. Also, 2 and 5 makes 7!" He used to use his fingers a lot when playing this game, but he’s switched to doing it in his head. He then gives me a number (usually much larger) and I model playing the game as well, talking aloud when I’m "figuring out" how to make the number he’s given me.

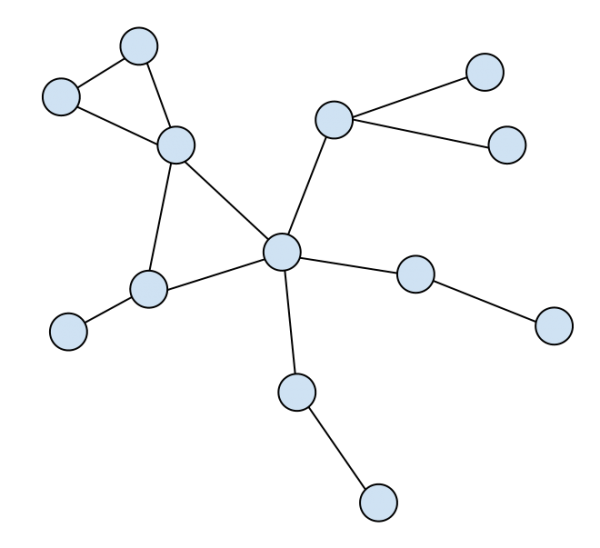

The point is, because I am mathematically numerate, I pass along this numeracy to my son through informal conversations and numeracy games. One cannot assume that simply because children have no formal mathematics instruction that they have no math learning. Our world is filled with mathematics, and the people who recognize that will share it with kids. By the time kids are 4 years old, they will likely have had literally thousands of interactions with numeracy.