I’ve been participating in Keith Devlin’s "Mathematical Thinking MOOC" hosted by Coursera. The purpose of my participation has been to evaluate the MOOC as a learning environment for my students. I want to see if we can find ways to bridge the gap between the type of thinking required for my students to be successful in their current k-12 environment to what it will take for them to be successful at the university environment, particularly in mathematics. We’ve already spent some time thinking about what they need for their success outside of school. I really want my students to think mathematically, so any resource I can share which will improve that will be valuable.

Unfortunately, I will not be suggesting the current version of Keith’s course for my students, but I will continue to follow the project to see if becomes something that will be more valuable for most of my students. Below is a critique which outlines some of my reasoning behind not recommending this experience for my students (yet).

I can separate my critique into three areas; user interface, course content, and course structure. I’m hopeful that this critique can be used to improve this experience for future students (or at least to have points I’ve brought up rebutted). Keith has mentioned many times that this is an experiment, and of course with all experiments, we try things out and see what works, and see how we can improve the experiment for next time.

User interface

This is likely to be out of Keith Devlin and his team’s control, but is worth mentioning because of how important it is for student learning especially in an online setting. It seems to me that something which is so crucial to how students develop understanding is so often outside of the control of the people responsible for their student’s learning. We spend an awful lot of time trying to improve learning environments for students in offline settings; we should spend at least as much time trying to improve learning experiences in online settings.

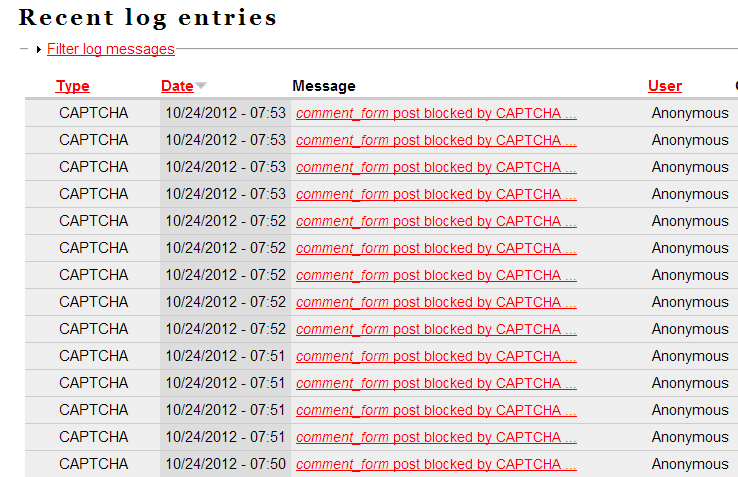

The course is basically divided into course videos, course problem sets, and discussion forums. The biggest problem I’ve noticed with this way of dividing the course is that there is no way for a user to know what videos they have missed, what problem sets they have not yet done, and who has replied to their discussion posts or comments without visiting all of these areas of the website each time. The system, of course, does keep track of this information, as it will let you know when you visit a particular lecture if you’ve watched it before, so why not aggregate this data for students?

The structure of the course is designed around containing the information in such a way which is easy for an instructor to follow but which should be re-arranged in such a way that the most relevant information necessary for a student is delivered to them. See Edmodo for an example of a fantastic user-interface which does exactly this. Courses, and the relevant user interface design for a course, should be designed around the experience of the user, not around the way the information is categorized by the facilitator of the course.

This user interface makes a difference. For example, one of the course suggestions is to join a study group for the course. As many of the participants of the course may be participating in isolation, making those connections and setting up a study group for one’s self is incredibly difficult. There are no spaces within the course where an effective study group could meet and discuss ideas. Given the emphasis placed on this by the course designers, this space should be woven into the structure of the course in a meaningful way. Improving the user interface so that it has more of a social feel, much like what Edmodo has done, would do a lot to improve retention of students through-out a course.

The course server itself crashed, just as Keith was set for students to complete the final exam for the course. This critique has nothing at all to do with the server crash, as this is outside of the control of Keith and his team. This is a problem that could have come up for anyone trying something so ambitious as to deliver a course for more than 50,000 people.

Content

When I heard that Keith Devlin was running a course on mathematical thinking, I had in my mind a much different experience than what has been offered. My students are exposed to formal mathematical reasoning of the sort offered in this course; in fact I have a student who is continuing learning about formal logic in university due to the interest in this area that arose as a result of my classroom. However, one thing which is often missing for my students is a result of what I like to call the black box approach in math education.

Here’s a story to explain what I mean. I had a professor in university who had a habit of giving lectures on how to solve specific problems related to concepts he introduced in class. Almost every single time, he made some error while presenting the solution to us, and ended up with some sort of impossible situation or contradiction. He would give up on his solution and say, "Okay, but you get the idea." He was always incredibly embarrassed, and he would promise to come with the correction in his solution for next class; which he always did. Unfortunately he created a black box around mathematical problem solving for us. I always wanted to know, given that I’ve found an error in my solution, what process can I go through in order to find my error and fix my work? This aspect of problem solving is usually not shared with students, and certainly wasn’t by my professor, often because of the complaint; we just do not have time.

So when I heard about a course about mathematical thinking, I thought that it would include more than just the formal symbolic portion of mathematical thinking and give students opportunities to learn what is in the black box.

I also recently watched a lecture by George Polya in which he describes the beginning of mathematical thinking as starting with a guess. What Polya attempts to do is to lead a group of students through an activity in which he tries to make his thinking, and his process of turning a guess into a certainty, completely clear. I know that this approach is something that many students never get to experience, and understand, and I was disappointed that there very few opportunities for students to see this type of approach discussed, or even modelled.

My hope was that students would be given some examples of mathematically challenging ideas and problems from throughout history, and given some of the tools to try and work out the solutions for the problems themselves, and more importantly, to have some of the creative thinking required for these solutions laid bare.

It is probably true that this may mostly be a matter of differing definitions and I may be being especially pedantic here. Obviously formal mathematical logic is a critical part of mathematics; I’m not trying to argue that. It is also true that many students are never exposed to formal mathematical reasoning in the current k-12 system. All I’m trying to argue is that there is more to mathematical thinking than formal logic, and that I would probably not have this complaint if Keith had labelled his course something like "Introduction to Formal Mathematical Reasoning."

Structure

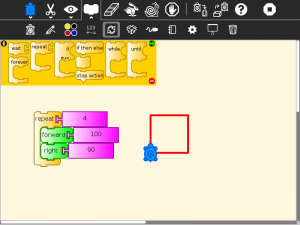

The course has a series of videos which have to be watched, and which include in-video quizzes, which have to be completed in order to gain course credit. There are also a series of problem sets which also have to be completed. In order to gain the certificate of achievement for the course, and a related course grade, students need to complete the quizzes and problem sets (submitted in the form of a solutions to a multiple choice exam). There are also problem sets which do not count toward course completion and have a much more open-ended set of solutions.

Despite the fact Keith has repeatedly said that people should not focus on the lectures and the quizzes, people continued to do so in the forum discussions, even taking the time to point out minor mistakes and omissions made. Why would they do this, if the teacher of the course is telling them not to worry too much about them? Quite simply put; when you place a series of tasks in front of people in the context of a course, they will naturally choose whichever of those tasks is most necessary for them to complete for credit. So even though the forum discussions and study groups could be a far more effective way for students to figure out how to solve the open-ended problems, they will focus on the lecture quizzes and problem set quizzes because these are what are necessary for completion of the course. For an example of platforms which put emphasis on the discussions, questions, and comments of their users (such as Keith wanted people to do as per his emails out to the participants of the course) explore Stack Overflow or Quora.

The course had time limits set for completing the in-lecture quizzes, and the problem set quizzes. It seems to me that this is completely arbitrary. Why set time limits when the quizzes are all machine graded anyway? We set time limits as teachers mostly for administrative reasons (it is really hard to grade a bunch of assignments that come in at different times) or as some would argue (can you tell I disagree with this argument?): "to teach people how to meet deadlines." Since neither of these is a concern for Keith and his team, I do not understand the use of the time limits at all, except that it replicates one aspect of what happens in an offline university course as well. My recommendation: set the time limits for the very end of the course, or perhaps a day or two earlier. This allows students to catch up without penality, which again would lead to a greater number of students completing the course.

The positive

I really liked the problem sets I looked at. Some of the problems given were so good, I shared them with colleagues from outside of the course. One of my colleagues incorporated some of the problems into her own classroom, and at one point three of us discussed one of the problems, and a possible solution to it, at length. The problems themselves were an excellent source of discussion, and I noticed a lot of strong positive discussions around the problem sets on the discussion boards.

Having an ability for people to have essentially unmoderated conversations around formal mathematical logic is excellent. The discussion forums were filled with people discussing the intricacies of formal mathematical language, and trying to explain these concepts to each other. It cannot be a bad thing to have thousands of people discussing mathematical ideas.

The distinction Keith made between how language systems work and how formal mathematical language works was an important point, which is often missed by people studying mathematics. We use formal systems for a reason; they prevent (or at least minimize?) ambiguity. Ambiguity in language is a problem that mathematicians struggle to avoid, and which the non-mathematician sometimes has no patience for resolving.

The peer review system for grading assignments is a very interesting idea, and one which I wish I had more opportunity to observe. I think that the idea of peer reviewing work in an online setting is a powerful one, as it allows us to move away from quantitative (and sometimes misleading) descriptions of student engagement and learning in an online setting, and move toward a more qualitative description of student learning. The numbers rarely give the entire picture when students are learning, and so anything that produces a different picture of that learning is valuable.

Summary

I think that creating an experience through which students learn mathematical reasoning is a terrific idea, and I’m impressed with the work Keith Devlin and his team did to work on such an experience. Many people I’ve spoken to think that the course content for Keith’s Mathematical Thinking course is excellent; I do not disagree, I was just hoping for a different emphasis.

I believe that online learning has the potential to be more centred around the needs of students, and connecting people in new ways, who learning similar information, but I think that the Coursera course structure has a long way to go before this will be easy to do in their environment. We don’t need to emulate the pure classroom experience any longer, we can create new experiences and allow students to learn material in wholly new ways.

I felt like there were a lot of positive aspects of the MOOC Keith created (as per above) and I look forward to keeping track of this project as it evolves over time. I’m also going to post a summary of an idea I’ve had around creating a space for learning mathematical ideas in an online setting. After all, if I am to critique someone else’s work, I should put my own work out to be critiqued as well.