Richard Feynman writes:

….

The lecture hall was full. I started out by defining science as an understanding of the behavior of nature. Then I asked, “What is a good reason for teaching science? Of course, no country can consider itself civilized unless… yak, yak, yak.” They were all sitting there nodding, because I know that’s the way they think.

Then I say, “That, of course, is absurd, because why should we feel we have to keep up with another country? We have to do it for a good reason, a sensible reason; not just because other countries do.” Then I talked about the utility of science, and its contribution to the improvement of the human condition, and all that – I really teased them a little bit.

Then I say, “The main purpose of my talk is to demonstrate to you that no science is being taught in Brazil!”

I can see them stir, thinking, “What? No science? This is absolutely crazy! We have all these classes.”

So I tell them that one of the first things to strike me when I came to Brazil was to see elementary school kids in bookstores, buying physics books. There are so many kids learning physics in Brazil, beginning much earlier than kids do in the United States, that it’s amazing you don’t find many physicists in Brazil – why is that? So many kids are working so hard, and nothing comes of it.

…

The obvious parallel to draw here is that Science and Math education in the United States from K to 12 (and to some degree other places in the world, like Canada) suffers from the same syndrome. Much of science and math is “taught” but not much of it is learned. If you argue with this premise, you need to ask only a few questions to convince yourself that this is true.

Who uses scientific reasoning and experimentation in their day to day life to solve problems? Who uses mathematics as a tool to solve and explore the richer problems of our world? The answer is, unfortunately, an abysmally small number of people. Such a small number of people in fact, that very few of them are in positions of power and authority, and much damage is done by people who do not understand science and math deciding on educational policy.

Only 14% of US citizens (compared to 59% of Canadians) believe that “humans being have developed over millions of years from less advanced forms of life, but God had no part in this process.” Most people you ask believe that the reason we have seasons is because Earth’s distance from the sun varies during the year. Almost no one uses algebra or calculus in their daily lives to solve problems, and even something as simple as the Pythagorean theorem is rarely used. Quite simply, the general population of both the US and Canada is largely ignorant of how science and mathematics is useful in their lives.

The fact that the US has such an innumerate and scientifically illiterate population is due to nothing else but the poor quality of science and math education over the years. I don’t blame science or math teachers (much) for this problem; in my opinion, it is a problem of a curriculum which attempts to squeeze too much into a few years, and which relies on regurgitation of facts as the primary means of assessment of understanding, rather than any other form of assessment. Further, in many schools experimentation and exploration of ideas is completely gone from the curriculum as the schools attempt to meet requirements of state and federal curriculums.

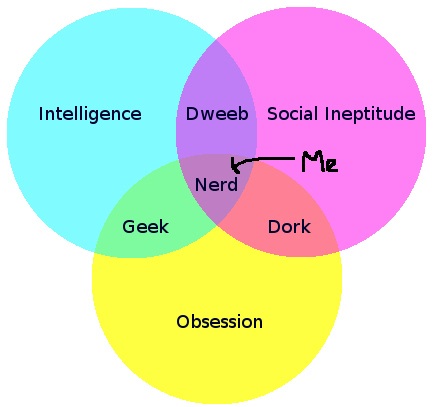

Everyone I meet falls into two classes of people; those who liked mathematics in school, and those who hated it. From personal experience, the latter group vastly outnumbers the first group, and almost everyone in both groups is pretty feeble at recognizing mathematics in the real world. Neither of these groups has been served by the education they have received.

We rely on a type of pseudo-teaching of ideas in science and math too much. Students can tell you that “the slope of the line is equal to the rise over the run” but couldn’t give you a single practical application of slope if queried. Students can list off the parts of a cell, but given an organism under a microscope they’ve never seen before, they would be hard-pressed to identify those parts of a cell in that organism. We’ve built a generation (or 4) of people who might be able to describe science and math in terms of other simpler mathematical concepts, but who could not identify those concepts in their immediate surroundings, and certainly never apply those concepts to the problems they face in real life.

For example, as I was walking on the street, I heard a man say to another, “That’s why I play blackjack. Cause if you play it right, the dealer busts every time.” This kind of misconception accurately represents the typical person’s understanding of probability, which is to say, not much. Casinos and lotteries get rich because of the ignorance of the people who play.

Why do we insist on teaching using methods which do not produce what we should want as a society; a public which sees the value in the “universal language” of the universe, and uses it on a regular basis to solve problems?