“I learn something and then we are tested on it, and I know I never to know it again, so I immediately forget it.”

A Grade 11 Student

It seems incredibly common to me. Teachers teach, students learn, teachers assess, and then students forget. But why does this happen, and why do we accept it?

The fundamental goals of education are to equip people with the knowledge and skills they need for the future, to open up their minds to what exists or could exist, and to help learners understand the world. If what students do is go through different cycles of learning and forgetting without anything being more permanently remembered, this makes that goal a fantasy.

There are three approaches that can be used to improve the odds that learning doesn’t fall into this trap.

- Make the initial learning unforgettable.

- Revisit the ideas previously learned over and over again.

- Connect everything learned to big ideas.

Make learning unforgettable

We all have experiences from our schooling days that have stuck. These days and moments stand out to us, typically because we have strong emotion attached or because the events were just so new and/or fascinating to us. I still remember sitting at a computer in our social studies classroom in the basement playing around with Logo on a Commodore 64 computer in the corner.

Can educators make learning like this? I don’t think so, at least not consistently, and not for all children. What makes one child feel a strong emotional response isn’t likely to produce the same response in all children. For every child who learned how to program computers from Logo, there are probably two more who found something else fascinating instead.

But educators can make learning stickier. These instructional strategies, which aim to make mathematical ideas explicit, also make learning sticker. They are almost all free to implement, and while not entirely straightforward, every educator is able to use these kinds of instructional moves.

Revisit ideas learned

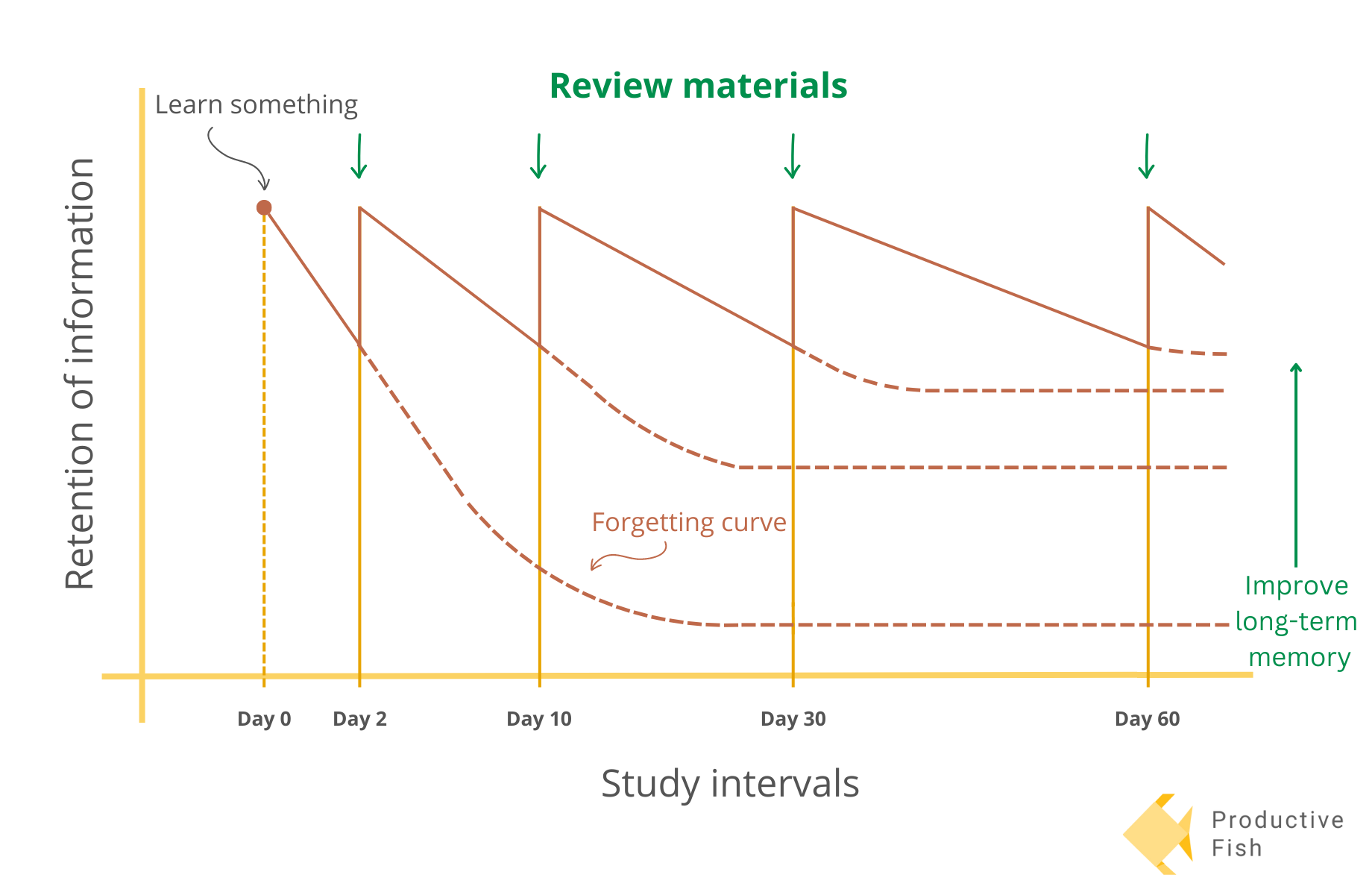

Since our brains are optimized to remember things that come up again and again, practicing using ideas is certain to cue the brain as to the importance and relevance of that material. There are some ideal ways to optimize practice, and none of these strategies is especially difficult to implement. They just require some careful planning to coordinate the timing of practicing ideas during the year.

This needs for practice is born out by many different research studies that show that the strength of our memories decays over time and that repetition is crucial to keeping our long term memories fresh.

The problem here is that one cannot practice everything; there just isn’t enough time. Educators have to be selective about what is practiced and what is likely to eventually be forgotten. However, this is where the next idea comes in.

Connect everything to big ideas

Another thing that psychologists have discovered is that the type of information one is trying to learn matters. Random information is much harder to remember than well-structured information, which is similarly harder to remember than information that is well-connected to things one already knows.

Ideally, educators should help students connect what they are learning to other things they already know. One strategy to do this is to connect the small ideas to be learned to bigger ideas already known. One big idea might be: “we can represent mathematical ideas equivalently in different forms”. A smaller idea that can be connected to this big idea is: “we can represent fractions like ¼ visually using a bar model with 4 equal parts and one of them shaded.”

This last idea is less straightforward, unfortunately. Coming up with the right big ideas is nontrivial and can take significant planning from educators. Many curricula out there do not make big ideas explicit, making educators’ work harder. While it is technically free to implement this, the planning load for educators is likely to be large, at least initially. This is where teaming up with other educators is critical to share the planning load.

If these strategies are so good, why aren’t educators already doing these things?

Like most things in education that seem like good ideas that aren’t being used, there are probably a variety of reasons. Using new instructional strategies is great, but educators need time to practice and prepare to use these strategies. Educators feel rushed to complete a long list of things people already think they should be teaching, so building in time for additional practice seems impossible. Educators are already short on time to finish planning all the things they are currently doing that adding one more planning task to the load with uncertain benefits seems unreasonable.

I’m not sure what the answer is here, except that I wish the curricula educators were offered had better support for these strategies. If the curricula offered suggestions for when to use specific instructional strategies, part of the planning load for educators would be already done. If curricula included spaced, interleaved, retrieval practice of the most critical ideas from the curricula, educators could much more easily implement this practice. If curricula explicitly named the big ideas of the curricula that connect together all the small ideas, then educators could spend less time trying to work these out and more time planning how to use these big ideas in their instruction.

Deborah Boden says:

Assigning Mixed, Spaced, Practice for homework is a game changer for retention. CPM structures their homework like this and our school has revised homework to be mixed, spaced also. We’ve found it almost eliminates the need for review before the School District Benchmarks and State Testing at the end of the year.

May 5, 2025 — 2:18 pm

Ursula Parken says:

This really resonates with how I’ve felt about teaching for lasting understanding instead of short-term recall. I love the emphasis on making learning stickier through emotion, repetition, and big ideas. It’s a powerful reminder that education should be about building durable knowledge, not just prepping for the next test.

June 12, 2025 — 7:15 pm